This article comes from law firm DLA Piper LLP and is authored by Francesco Novelli and Natasha Luther-Jones.

In London and May 2017, DLA Piper convened a global gathering of around 150 guests to discuss the opportunities surrounding the emergence of battery storage in the global energy sector, Battery Storage – A New Frontier.

There is a huge amount of interest in battery storage and a lot of talk about it. Growth in battery storage is being fuelled by a reduction in costs and wide recognition of the value of storage. Yet, the market is still in its infancy and there are equal amounts of uncertainty. Does it have the potential to disrupt the energy market? Will the market become highly competitive as soon as there is a breakthrough? Will those who take a risk now better position themselves for the future? It is fair to say that at the moment we really don’t know.

“There is a huge amount of interest in battery storage and a lot of talk about it.”

What we do know is that battery storage projects are successfully coming to fruition in a number of countries, primarily the US, Australia, and Germany. Here we discuss the key themes surrounding the opportunities and challenges with battery storage and discuss its potential to be a game-changer that will revolutionize the global energy market.

What is it?

Battery storage creates the ability to store power at times of excess and release it at times of deficit and high demand, which is critical to balancing supply and demand in the power system. As the fossil fuels of the past, that have been so reliable yet so damaging, are gradually phased out, the rise of clean energy sources such as wind and solar present a new problem, a problem of reliability and security of supply.

Raising the low-carbon game

Battery storage offers the opportunity to raise the game on the vision of a low-carbon global economy. Supporting the growth of renewables, batteries are starting to play a significant role as peaking plants, particularly in countries like Australia, where over recent years whilst power generated from renewable sources has boomed, managing the fine balance between supply and demand has been tricky, to say the least. Batteries have started to play a key role supporting the growth of renewables in Australia.

Significantly, the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), a government agency, is providing subsidies for storage facility projects, making Australia a prime and attractive market. Here, DLA Piper and Nord/LB, the German bank, have worked together on the Lakeland Solar and Storage Project in Queensland. This is a 13 MW Solar PV and 5.3-MWh battery storage cogeneration facility that was financed in part by ARENA and a loan facility from Nord/LB – the world’s first utility-scale solar and storage project, which became a reality in 2016.

The question of funding

Despite the overwhelming interest in battery storage, the costs associated are high and until demand increases, for many projects, funding continues to be a challenge. Funders are treading carefully, mindful of the “Winner’s Curse” if projects have not been subject to proper due diligence.

Battery storage is thought to be two to three years away from real competition with established technologies. For example, Powin Energy’s Stack140 is a modular, flexible, purpose-built 140kW battery array that the company says is easily and cost-effectively scalable from 125 kW to multiple megawatts using indoor cabinets or 20 or 40-foot containers for outdoor installations.

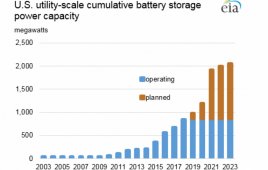

On the up side, funders are starting to show their appetite and now appear more willing to take merchant risks than in previous years, even though some battery projects require a leap of faith. Use of energy storage in the U.S. is growing quickly, where funding is considered to be less of a challenge.

Energy storage deployments in the U.S. totaled 336 MWh in 2016, doubling the MWh deployed in 2015. IHS Technologies predicts that up to 6 GWs of storage will be installed in the U.S. annually beginning in 2017 and that 64% of such installations between 2012 and 2017 will employ lithium ion batteries.

Each of Navigant and Bloomberg Energy predicts the current cost of large-scale batteries will go down by approximately 57% to 60% by 2020 while the Energy Storage Association estimates costs for battery-based storage have reduced by as much as 70% in the last two years.

The U.S. is no doubt leading the way with funding success, especially in California where it has been possible to create financing deals based on market terms that create revenue streams, which project financing providers look to provide. This is illustrated by a recent deal that DLA Piper advised on, in which Macquarie Group secured funding from CIT Bank to partly fund a $200m portfolio of storage systems in California – the largest battery project to get bank financing in the U.S., which came to a financial close in March 2017. What has really made this deal workable is a 10-year capacity payment contract and without this, it is unlikely the deal would have come together.

Contract tenure

Whilst the CIT Bank/Macquarie deal in California was based on a 10-year contract, the UK market is emerging but requires longer-term certainty. Such 10-year contracts are not yet in sight. At the time of our forum, Element Power, the developer, announced the sale of its 25-MW battery storage project to Enel, the Italian utility giant. Element Power’s battery project had been one of the successful bidders in the National Grid enhanced frequency response tenders in 2016 in which four-year contracts were awarded to providers of power that can be dispatched in 1 second when demand is high.

So what happens after four years? Contracts are retendered and some take the view that there is value in having an operational site, even at the expiry of a short term contract particularly if it is a good site, close to a generating source. One thing that is clear, is that longer-term contracts in the UK will be a critical factor in driving down the cost of capital in the market.

Competition

How does battery storage compete with alternative, flexible sources of energy? Well – it is competitive to say the least. What we are actually seeing at the moment is a head to head technological competition between battery storage, peaking plants and other sources of flexible power. In the short term, reciprocating gas engines are likely to compete the hardest with batteries and will dominate the satisfaction of energy demands. Battery storage is thought to be two to three years away from real competition with established technologies. The key revenue stream in the meantime is thought to be through arbitrage.

Optimization

How battery storage schemes are optimised to maximise revenue stream is a major concern. The use of software and cognitive learning is necessary to assess and optimise the use of battery storage to really utilise the energy consumption on the site to maximise revenue streams. This is particularly relevant with revenue stacking and assessing offtaker needs.

The lifecycle

The market is cognisant of battery degradation, which is affected by the number of cycles the batteries are charged and discharged. At the end of life stage, the European Commission has a requirement called the Battery Directive which dictates that the batteries be disposed of in an appropriate manner.

The liability is usually placed upon the manufacturer of the batteries and battery recycling companies are typically used to salvage what they can, focusing on materials like copper or aluminium that could be of value and partly defray the cost of disposal – everything else is essentially scrapped. While manufacturer’s warranties are usually part of the deal and are intended to assist with such risks, lifecycle costs are relevant and should be factored into the financial modelling of any project.

The safety of batteries also has to be considered. So far they have tended to be installed in remote locations, usually unoccupied by people. As the industry grows we are likely to see greater proximity between the battery and occupied spaces, spaces where people are living and working. At this point in time safety and certifications will have to factor in storage projects.

Filed Under: Energy storage