Chris Baker, Adams Product Manager at MSC Software

The size and displacement of the Ballast Nedam drilling rig presented complicated engineering problems to the Anholt wind farm construction crew. They had to remove boulders from wind turbine monopile sites, and the rig could only travel and operate in seas with a maximum 3-ft wave height. Engineers had to determine optimal cable tensions for securing it during transit, avoid collisions between parts, erect it on the monopile sites, and secure it at proper operating angles.

Any wind-power project is an engineering challenge, but offshore projects present the additional challenge of a hostile environment. Designing pylons and turbines that can withstand the marine environment is the first challenge. Building those designs on the open sea is the second, and perhaps more daunting challenge.

The Danish engineering firm Knud E. Hansen A/S (KEH) faced this challenge during construction of what will be Denmark’s largest wind farm when it is completed this year. KEH was contracted by one of the companies building the Anholt OffShore Wind Farm to determine the safest way to move a drilling rig to multiple wind turbine sites on the open sea and then secure it in operational positions.

The firm used computer-aided engineering software commonly found in automotive and aerospace design to test complex mechanical designs. The results are encouraging for wind power companies seeking to control costs by anticipating site conditions and planning around them.

Anholt Offshore Wind Farm is a $1.8 billion wind-energy project in the Kattegat region of Denmark. Anholt consists of 111, 3.6-MW wind turbines located on pylons built in 50 to 60 ft of water. The Anholt Offshore wind farm will have capacity of 400 MW once it goes on line, providing enough electricity to meet about 4% of Denmark’s total electricity consumption.

The pylons’ foundations are monopiles with 16.5-ft diameters and walls 2 to 3.5-in. thick, and 121 to 177-ft long, depending on location, and can weigh up to 460 tons. Hydraulic hammers drive the monopiles 60 to 120 feet into the seabed.

Among the challenges of building Anholt was a seabed studded with boulders in the paths of the monopiles. Every time crews located a boulder in a monopile’s path, they had to call in a drill rig to remove the boulder. By the time all the monopiles were driven into the seabed, crews moved 5,000 obstructions.

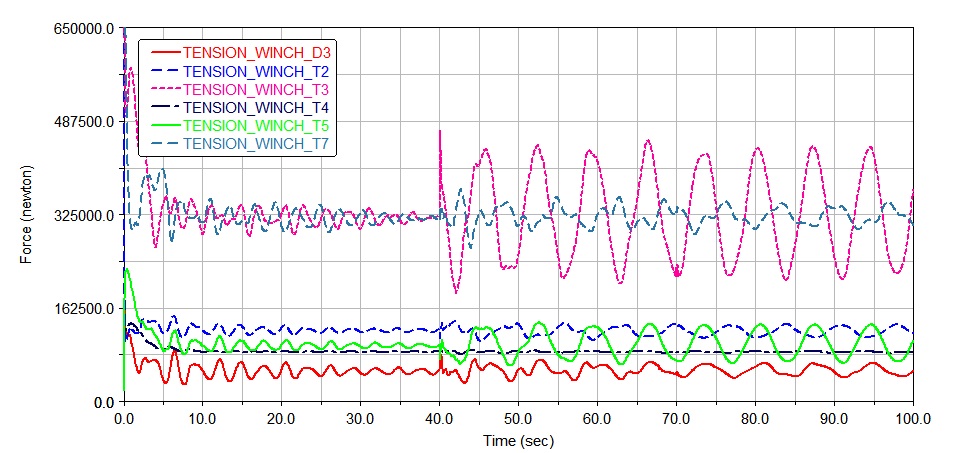

By simulating the positioning of the drilling bit, MSC/Adams could calculate the tension on the winch lines.

The drill rig could only be transported and operated safely in seas with waves three feet high or less. In rougher seas it had to be removed to sheltered areas to avoid damage. Each move risks damage to the rig, so project engineers had to create a strategy that would minimize risk. They had to prevent:

- damage to components of the rig that had to be lashed in transit

- excessive stress on the winches that secured the cables during transit and operation, and

- collisions between parts of the drill rig.

They also had to ensure enough clearance between the drill rig and the ship transporting it so the ship’s crew could reach the underlying deck. Finally, there was an operational issue to manage. Once the drill arrived at each monopile site, the angle between the drill extension and the bottom of the drill rig could not exceed 6.8°.

The construction teams used simulation software from MSC Software to build a model of the drill rig and the components of the crane assembly that lifts it into position: lifting spreaders, lifting and lashing equipment. They imported the model into MSC Adams multi-body dynamics software, which simulates the behavior of moving parts in complex systems.

KEH Marine Engineer Mirco Zoia used the software to study how loads and forces were distributed through the mechanical systems when the drill rig was in motion. He added densities and other material properties to the model imported to Adams. All of the parts in motion were joined together with translation, revolving, spherical, and cylindrical joints to simulate the rig’s behavior in transport and setup.

Zoia defined the steel and fiber ropes as flexible dynamic bodies with the same materials properties as the actual ropes, and other structures using pre-loaded models. He applied motions, constraints, wind forces, and wind loads to the drill rig model to simulate worst-case conditions. This analysis lets him assess the drill rig’s maximum displacement and the minimum required, winch-pulling force to satisfy operational and safety requirements.

“The multi-body dynamics analysis helped us understand the motion and forces involved by capturing the full gamut of real-world complexities, including rigid bodies, flexible bodies, springs, dampers, joints, and all other mechanical components,” says Zoia.

“The software never placed limits on what I wanted simulated and made it possible to quickly assemble the complex model. Every part of the construction could be visualized during the simulation and the plots of the results easily displayed. All the wave motions have been applied to the dynamic system to study dynamic behavior in detail while ensuring the safety of the marine operations, reducing risks, and controlling installation costs for the wind farm.”

The Adams analysis lets engineers create arrangements for lashing the drill rig to the transporting ship and securing it in place at the monopile sites that:

- did not exceed the six winches’ braking capacity

- prevented collisions between parts

- let the ship’s crew reach equipment on the deck under the drill rig

- did not exceed the 6.8% maximum allowable operational angle, and

- kept the proper loads on the winches to hold the drill rig in position.

The Anholt project is expected online in 2013, as predicted when announced. KEH’s multibody dynamics and motion analysis contributed to keeping the project on schedule by letting construction crews to move and set up the drill rig in choppy water without the risk of damage. As offshore wind becomes a more attractive renewable energy option, high-end analysis can help hold down costs, raise safety levels, and keep projects on schedule.

Chris Baker is a product manager at MSC Software, a developer of simulation and analysis software based in Santa Ana, Calif.

Filed Under: News, Offshore wind, Projects

I had an experience of working on msc software with my team. This is definitely an awesome toll for all engineers and project managers.

Dear Chris, Dear Paul

I do like the article but being working at the owner of the HLV Svanen (Ballast Nedam Offshore) I would like to correct a few disturbing and incorrect parts.

The HLV Svanen is not a drilling rig. It is a Heavy Lift Vessel and was designed to build bridges and has done so in Europe and Canada (Confederation bridge). Maximum lifting capacity of 8.700 tons which makes it one of the largest in the world.

For offshore wind we use it since 2006 for the installation of foundations, the so called monopiles. We have installed approx. 360 monopiles so far, including the largest monopiles so far, weighing up to 805 tons. Later this year we will install piles up to 950 tons. At Anholt we have driven the 111 monopiles as well using the HLV Svanen.

The seastate you mention is not correct. The HLV Svanen installs foundations in between a significant waveheight of 1,0 – 1.5 meter (3,3 to 5 feet) and we have to look for shelter if we expect significant wave heights over 2,5 meter (8,3 feet). This gives us a much larger workability then shown in the article.

I would welcom if you could correct the article according to the facts and look forward to answer any additional question you might have,

Kind regards

Edwin van de Brug

Commercial Manager Ballast Nedam Offshore