Two undergraduates at the Georgia Tech School of Architecture recently claimed top honors in a competition to aesthetically combine land art and electrical generation. James Murray and Shota Vashakmadze’s design, called Scene-Sensor, would rise 90 feet over New York’s Freshkills Park and annually produce an estimated 5,500 MWh.

Two undergraduates at the Georgia Tech School of Architecture recently claimed top honors in a competition to aesthetically combine land art and electrical generation. James Murray and Shota Vashakmadze’s design, called Scene-Sensor, would rise 90 feet over New York’s Freshkills Park and annually produce an estimated 5,500 MWh.

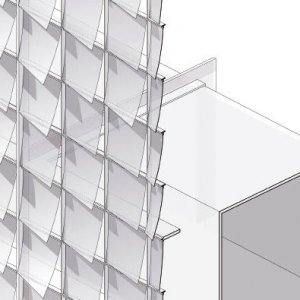

The students say two mounds in the park with a creek between them channel strong wind flows. The 720-ft long Scene-Sensor would intersect the flow and produce a shimmering spectacle that captures its energy with a metallic mesh containing piezoelectric wires. Visitors could also generate electricity by walking on a nearby bridge, activating ground piezoelectrics.

At night, Scene-Sensor would light up and envelop visitors who climb its internal walkways to the top, where a view of New York City would await. Both students currently work at a Georgia architecture firm and have plans to enter graduate school. WPE

Scene-Sensor is an land art generation design by two students at the Georgia Tech School of Architecture.

How it works

Scene-Sensor would use an estimated 208,000 small reflective panels to capture the wind. Each would be embedded with piezoelectric wires, which convert mechanical energy to electricity when they are stretched. Scientists aim to produce energy-generating textiles with this technology, but the students believe it could be applied to a larger framework. In this case, the wires would bend as thousands of metallic panels fluttered in the wind. Such a design would require less air movement than conventional wind turbines.

Extended Q&A with James and Shota

To better understand this project, we asked some questions via e-mail. Below are the responses from Scene-Sensor designers and architecture students James Murray and Shota Vashakmadze.

Is this primarily a work of art or a way to create electricity?

It’s always been about making an audience realize how the two can work together, combining an artistic imposition with the pragmatic necessities of renewable energy generation, creating an art installation out of generating electricity. Scene-Sensor maps and illuminates flows of both people and ecologies of Freshkills caught within and between, and shows the energy potentials that they each carry.

What kind of wind resources are available in this landscape and how are they appropriate for this type of project?

From wind resources provided by LAGI, as well as surrounding weather data, we were able to model and analyze the landscape as a field of wind flows. We found that the two mounds of the park created a channel along the valley of the creek. Wind would constantly be moving over the channel formed between the two parks, creating an ideal site to bridge across and collect wind energy.

With what material would the metallic mesh be made and how reflective is it?

With what material would the metallic mesh be made and how reflective is it?

We decided to use a flexible, woven steel substrate for the piezoelectric wires as it would be efficient for energy gathering and would also give us the best reflective quality a mesh can produce. An individual panel would reflect the basic colors of its surroundings but as a screen, the matrix of panels intends to act as a mirrored mirage of the fluctuating environment of Freshkills.

What’s your estimate of how many of these small panels the scene sensor would contain?

At the dimensions we had been working with, it would add up to 208,000 panels.

How would you describe the way the panels and wires interact with the wind to create energy?

The wires would be embedded in the panels, woven within the steel of the mesh, and would bend as the it fluttered in the wind. It is this compression and expansion of the material from the bending that would be translated to electricity. The advantage to normative systems would be that such a small scale panel needs much less wind to begin creating energy. It could work from minute fluctuations in the air currents, while other methods of harvesting wind energy need a higher threshold to begin to function [a cut-in speed needed to start moving the turbine].

Piezoelectic energy is often employed in small-scale projects. Is there any evidence that a large-scale project like Scene-Sensor would function in the way you propose?

The research currently being done [at Georgia Tech, among other institutions], is working mainly toward finding ways of incorporating the piezoelectric wires into fabrics, working toward a goal of energy-producing textiles. It would definitely need to be done at a small scale, but the promise of the Scene-Sensor is that it can take such small scale operations and assemble them into a larger framework. So it would not be about the scalability of the technology, but about the scalability of the supporting structures. Operationally, it would be a network of many small-scale generators, assembling into a whole that is more than the parts.

Where would the energy go once it’s created?

As per the competition brief, a power substation would be provided by the park to collect all energy generation.

How did you arrive at the amount of energy made with this machine (5,500 MWh)?

We projected from the site’s wind data, and worked according to the efficiency rates promised by the technology. For the ground piezoelectrics, we calculated the potential traffic across the bridge relative to energy generation rates from similar implementations and proposals.

We projected from the site’s wind data, and worked according to the efficiency rates promised by the technology. For the ground piezoelectrics, we calculated the potential traffic across the bridge relative to energy generation rates from similar implementations and proposals.

How large is this project?

Scene-Sensor is 90 ft. tall aligned to the height of the mounds flare stations, 20ft wide to allow for crossing ramps to carry people to up to views of New York City, and 720 ft. long to bridge across the boundary of the tidal channel between the East and North mounds.

Do you have any idea what a project like this may cost?

It is uncertain at this point, since the technology is not manufactured in large quantities. We will have a much clearer picture once the production processes evolve.

“A mesh of lights occupies the space between the two wind planes, displacing these flows in space and time. As evening sets in, these points replace the screen’s reflections of the daylight, displaying a memory of the generated energy to be viewed from within and without.”

Just seeing if I understand this correctly: There are sensors on the bridge that will project, after sunset and via a mesh of lights within the sensor, what happened on the bridge earlier in the day?

Correct. Overlaying the motion of the existing bridge onto the flows of people walking up and across the Scene-Sensor.

Do these sensors on the bridge also generate electricity included in the energy quote for the scene sensor?

Do these sensors on the bridge also generate electricity included in the energy quote for the scene sensor?

Yes, they do.

Finally, a bit about you. What are your years and majors at Georgia Tech?

James: I graduated in May of 2012 with a Bachelor of Science in Architecture with Highest Honors. I am currently working at Gamble + Gamble Architects in Atlanta with the intention to enter a Master’s of Architecture Program in the Fall of 2013.

Shota: I am graduating this semester [May of 2013] with a B.S. in Architecture. I am also working [though part time] at Gamble + Gamble Architects, and hope to be in graduate school next year.

I get the impression that you two are close. How did you come to know one another?

We got to know each other through Georgia Tech’s Barcelona Program as well as collaboration with a student-led design collective within the College of Architecture called gray_matter(s). Through gray_matter(s), we have co-edited an online publication as well as designed and built site-specific installations for exhibitions within the Institute and the City of Atlanta. We chose to work together on the Land Art Generator Initiative Competition through a studio project at Georgia Tech directed by Fred Pearsall knowing that we would have to work as a singular unit addressing all disciplines in order to compete with teams of experts of architecture, landscape, and engineering. We hope to continue collaborating together throughout Graduate School, as we are propelled by this interest in Ecological Architecture towards our professional careers.

This project sounds exhaustive. What was working on it like?

Exhausting but in an empowering sort of way. We were proud to look back at our proposal organized onto the four competition boards acknowledging how far we had come.

How many hours went into its design?

We thought about the design constantly from our introduction to the competition in January right up until we submitted our proposal in June. To be honest, we are still thinking about the design and reality of the Scene-Sensor.

What about inspiration for this project — where did that come from?

The Scene-Sensor evolved from the complex series of constraints given to us by the competition’s organizers, Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry, as well as the broad understanding of architectural frameworks in terms of land art, ecology, biomimetics, and energy generation we explored during our studio with Fred Pearsall. WPE

Filed Under: Turbines