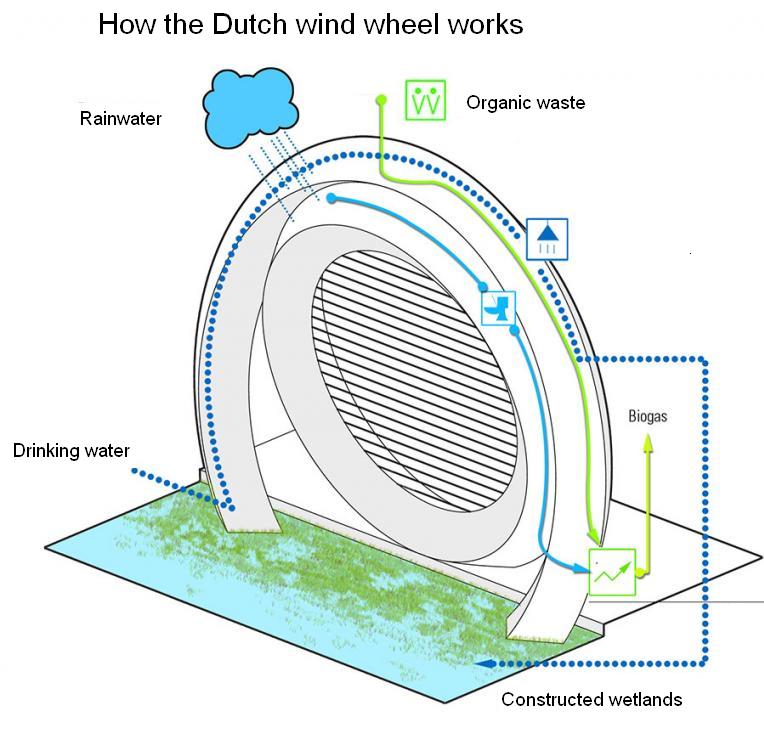

Rainwater is captured atop the structure. Tap water is fed into the wetlands that surround the Windwheel. Biogas is produced from the residents’ waste.

A Dutch Windwheel is an ambitious idea from the Dutch Windwheel Corp, a consortium of Rotterdam based companies. The wheel makes use of EWICON (Electrostatic wind energy converter) technology. In this arrangement, a wind turbine converts wind energy within a framework of steel tubes to electricity without moving mechanical parts, noise, or moving shadows. However, the company posts no power production figures.

The bladeless turbine works with the movement of electrically charged water droplets to generate power. It can be installed onshore and off, or mounted on a building. The design consists of a double-ring construction with a light, open steel and glass construction. The foundation is underwater so it looks as if the wheel is floating. Developer Inhabitat says the outer ring houses 40 rotating cabins on a rail system, while the inner ring, a windmill, a panorama restaurant, apartments, hotel rooms, and commercial outlets.

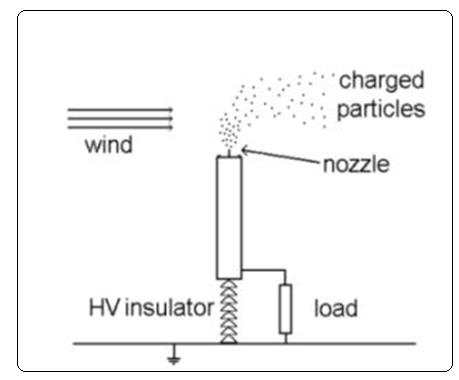

In a nutshell, the wheel works by charging positive particles, water droplets in this case, and letting the wind blow them away from a negative ion collector. This video does a decent job explaining the principle of operation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?Feature=player_embedded&v=tqkschwrobu

Of course, in real life, it’s a bit more complex. A demonstration unit constructed by the architectural firm Mecanoo is now on the Delft University campus. Because EWICON has no moving parts, the only pieces that can wear are nozzles that spray water droplets which serve as charge carriers. As Mecanoo describes it, the hardware consists of a flowing steel frame in the shape of a squared -0- supporting a framework of horizontal steel tubes. Electrically charged droplets are created within the framework and are blown away by the wind. The movement of the droplets creates an electric current, which can be passed on to the grid.

Earth acts as the collector in the EWICON system. The system itself is insulated from earth and the dispersal of charged particles will increase the potential of the system.

Many details pertaining to principles of the device’s operation can be gleaned from a dissertation developed by Delft researcher D. Djairam. As Djairam writes, allowing the wind to force charged particles against the direction of an electric field boosts the potential energy of these charged particles. The charged particles can then be collected in a charging system that is insulated from earth. Because the charging system starts out electrically neutral, dispersing charged particles causes its potential to rise. Basically, the earth acts as the collector for the charged particles.

Earth acts as the collector in the EWICON system. The system itself is insulated from earth and the dispersal of charged particles will increase the potential of the system.In theory, the charged particles could be anything that could hold an electrical charge. But water droplets turn out to be the most practical way of dispersing streams of charged particles, says Djairam. But there’s a limit to the amount of charge that a liquid droplet can hold before it will break up into smaller droplets, and that charge depends on the natural surface tension of the liquid. Evaporation is also an issue because the charged droplets need to survive until they reach the earth.

One wonders how much water would be necessary in this scheme to generate meaningful amounts of power. Here’s how researchers approached this issue: They calculated the work done on a droplet by the wind using some reasonable assumptions and came up with about 1.13×10-8 J. Assuming t a spray nozzle dispersing about 107droplets/sec or 20 ml/hr (not unreasonable, they say) gives a power associated with this stream of droplets of 113 mw/nozzle. A 30×30 array of these nozzles would produce about 102 W. Assuming water droplets with a diameter of 5 μm charged to 70% of the maximum theoretical charge (given by the Rayleigh limit), the rate of charged droplets is 8.5×107/sec, corresponding to a current through each nozzle of 4.7 μa. This would imply an output power of roughly 0.5 W into an electrical load of 20 GΩ. For the full explanation refer to the dissertation above.

Http://thedutchwindwheel.com/en/index

Filed Under: News, Turbines