This well worn blade has been ignored too long and will take more than epoxy putty before its turbine returns to service. Proper leading edge protection could have prevented the damage.

If a maintenance crew repairs the leading-edge erosion on a wind-turbine blade early enough with the durable cover produced by IER Fujikura, it could be the last time the problem is dealt with. That is the message from the manufacturer of Blaid Protective Sheet, a reinforced polymer material designed for a blade’s leading edge.

The standard kit the company produces covers about three meters of the blade’s leading edge (larger lengths available), and adds only about one pound per turbine collectively to the blades. What’s more, says IER Fujikura Technical Sales Representative Mario Mastroianni, “the material’s adhesive has a wider temperature-tolerance range than conventional materials, so it extends the working season. That should be good news for crews.”

What’s not so good is the awful beating that blades take. “The tips even on modest 1.5 MW turbines with 77-m rotors easily hit 100 mph along with dust, dirt, salt spray, sand, and in some places abrasive agricultural debris that gets airborne.”

Once the pitting and holes begins, the performance of the blade degrades and eventually, power production suffers. If this damage goes unnoticed the costs of repair could be astronomical,” says Mastroianni. As more large turbines find work offshore, blade problems could well be worse on their larger, faster tip-speed rotors.

When the damage is ignored long enough, suggests Mastroianni, the most costly repair might be a blade replacement. “One estimate for such an on-shore repair could be $100,000, that includes the cost of the new blade, transport to the site, cost of a crane and crew to install it, and lost production output.”

The wind tech applies a straight section of the cover. One kit has enough material to cover three meters of blade edge.

Most leading-edge repairs are made with an epoxy putty and a gel coat, simple but time intensive. As damage severity increases, so does the required time and cost. The ideal repair would be a one-time task, but most conventional repair materials will require reapplication in a few years at best.

Mastroianni suggests a better material. Although he’s mum on the exact composition, it appears about 1.5-mm thick, gray on the outer surface with an adhesive on the other. “The advantage here is that a technician need only clean the surface with alcohol, apply the cover which can be removed and repositioned when necessary, roll it tight, and let the bond form.

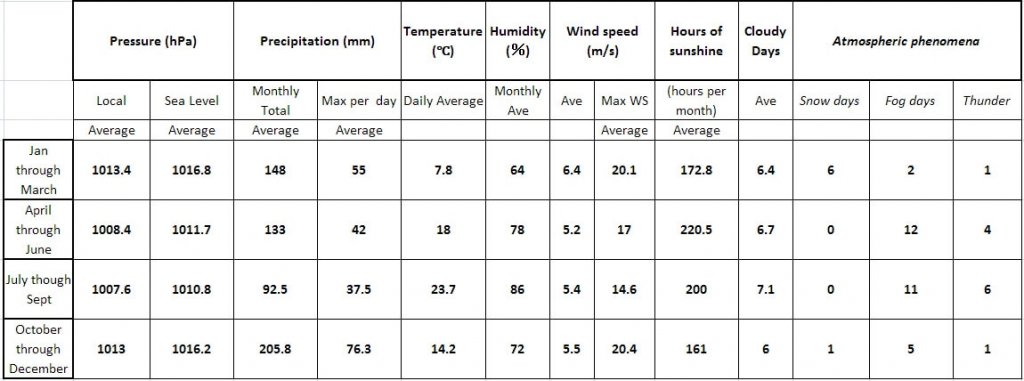

Most of the turbines in Japan that are flying the IER Fujikura covers are near or on the coast. Weather data for the pictured site is in the accompanying table.

After a few minutes from the time installed, it will not come off, without applying significant force.

Turbines in Japan have been flying with the material for over five years and without measurable degradation, he says. Test results from one of the five-year-old covers removed from one of those turbines appears below in From the lab.

The adhesive’s wider temperature tolerance over conventional repair materials let maintenance crews start repair work earlier in the year and work later. However, repair crews that are paid by the job may not be as interested in the development, but crews under contract should find the material a welcome addition to their toolbox. At this writing, Mastroianni says crews are installing the material on turbines in Texas.

From the lab

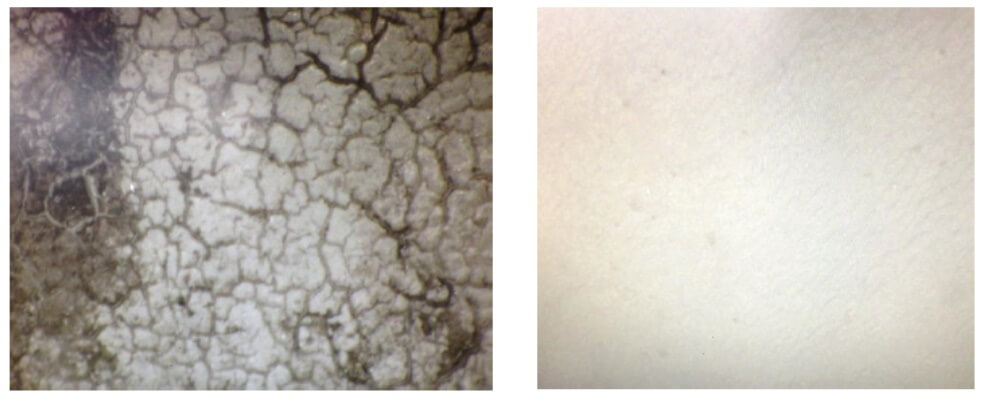

Cross section and surface observations from material in service for five years

A section of Blaid Protective Sheet, the leading-edge cover produced by IER Fujikura, was removed from a turbine after being in service for five years. Cross sections were made and compared to a new piece of material. A cross section of the used piece and new material were magnified 175 times with stereoscopic microscope to observe and measure the thickness of the rubber surface.

The worn material measured 722 µm while the new material measured 711 µm. No significant change in thickness was seen from worn to new. Based on these finding, it was concluded that wear does not produce thinning.

The material’s surface was also photographed under a magnification of 175 times with a stereoscopic microscope. The dirty surface was then cleaned and rephotographed.

The picture of the worn surface, below (left) shows dirt and grime accumulated after five years in service. Once the surface is cleaned, however, it shows no cracks or roughness. The integrity of the Blaid Protective Sheet has not been compromised.

Filed Under: News, O&M, Offshore wind

What companies apply this material to blades. I am looking for some costs on our own leading edge erosion.