A considerably different turbine tower and how its manufactured can reduce the structural steel content by at least 50% over conventional designs, resulting in a large drop in manufacturing costs, says inventor Ed Salter, CTO and cofounder of Greenward Technologies

A thin-steel tube in Salter’s design has been fitted with external reinforcing steel, capped, and pressurized.

, Austin Texas. What’s more, he says, the tower is almost “typhoon-proof”. After developing the idea of counter-rotating quad arrays of wind turbines, which may hold an answer to wind-turbine-wake-turbulence problems, Salter turned his attention to the conventional tower that holds turbines.

Wind-energy developers now prefer tubular-steel towers over lattice towers, even though the tubular towers typically use about twice as much steel for a given rating. But Salter says tubular steel towers are inefficient because of their tendency to buckle on the compressive or downwind side while tensile stress in the upwind side is still a relatively small percent of the steel’s yield strength. Buckling, he says, starts with an elastic instability of the relatively-thin steel shell, and can progress rapidly to catastrophic failure.

After applying the concrete composite material, it is allowed to dry before releasing the pressure. End flanges allow fastening one section to another.

However, a tower design called ISO-e, says Salter, reduces the amount of steel used in the construction of tubular towers by at least 50% while gaining a large increase in the tower’s survival wind speed.

Salter says the design is based on several established principles, the first being that a pressurized cylinder can withstand higher bending loads than one unpressurized. “The reason is that the pressure stabilizes the relatively thin steel shell by maintaining its shape, and opposing the inward elastic instability that precedes buckling failure.”

Secondly, he adds, it uses the advantage of prestressing concrete to provide optimal use of the concrete composite (residual compressive strain) and steel components (residual tensile strain), and preventing the concrete-composite material from experiencing any tensile stress, even under worst-case loading.

Thirdly, a thick reinforced and prestressed concrete composite jacket on the outside boosts the area moment-of-inertia of the outer jacket over 10 times that of the inner shell alone, so the outer jacket carries nearly all bending stress. Vertical loads on the tower and wind turbine will be distributed nearly-equally between inner shell and outer jacket.

Each tower section would start as a tapered steel tube similar in appearance to current towers. However, the steel would be about 1/3rd as thick. Oversized end flanges would use a conventional means of internally bolting the tower sections and would also extend beyond the OD of the steel tube. A suitable exterior assembly of reinforcing steel would then be welded in place. After an inspection, the tower section would be sealed with endcaps and gaskets, and each end fixed to a set of motorized rollers. The proprietary concrete-polymer layer would then be applied. Salter says the optimized mix for this application would be significantly lighter than conventional concrete. Pressure is slowly released after the outer jacket has cured and its stored strain energy becomes optimally distributed between the shell and jacket. Salter says the name “ISO-e” alludes to the equal-but-opposite shared strain energy, which increases the tower’s resistance to buckling. The design provides the same benefit as internally-applied pressure while ensuring that the concrete composite jacket never experiences tensile stress.

Weight estimates for a finished tower are about the same as a similar, all-steel tower. Key to achieving this is in the density of the concrete–polymer composite. Manufactured in standard-length sections, the completed tower will have a higher damping ratio than conventional all-steel construction which will reduce tower sway and provide for large reductions in radiated noise levels. In addition, a thin, chloride-resistant outer layer may be applied to towers headed for offshore or near-shore installations.

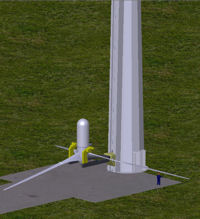

The turbine concept from Greenward Technologies puts four generators, a Quad Array, on the end of X arms. "Crane-less" servicing, integral to Quad Arrays, uses a built in fork lift to robotically pick up a modular turbine with the Array Frame (the X arms) rotated to a service position, before lowing the turbine to the ground. The technique keeps technicians from having to scale towers in inclement weather

The Fork Lifter has rotated a modular turbine so its shaft is vertical and has delivered it to ground level.

Filed Under: Turbines