This article comes from the UK firm EY ( Ernst & Young LLP) and is authored by Ben Warren, Partner, Corporate Finance – Energy

The green bond market is helping to channel growing volumes of capital toward environmental infrastructure. But how do issuers access this financing, while addressing any investor concerns?

The green bond market is on a tear. In the first seven months of 2016, $48.2 billion of green bonds were sold by corporate, supranational, municipal and government issuers who promise to direct the proceeds toward environmental ends. That figure compares with $41.8 billion for the whole of 2015, up from $11.5 billion in 2013.

In most cases, these bonds offer the same yield as comparable conventional debt from the same issuers — all but guaranteeing that they will be snapped up by a growing cohort of institutional investors keen to add a green tinge to their bond portfolios, with no financial penalty, or who are attracted by the risk-return profiles of the underlying projects. But many investors remain on the sidelines, unaware of the benefits, or even concerned with the quality of some issuances in this new market.

With the exception of recent central bank guidance to Chinese issuers, the green bond market is as yet unregulated; it is up to the issuer to declare how the bond proceeds will be used, and up to the buyer to decide if they consider them sufficiently green. With initial issuance from supranational financial institutions such as the European Investment Bank and the World Bank, investors could be confident that green bond proceeds would be used appropriately; as the market broadens to less well-known names, the risk of greenwashing rises.

“There might be reputational benefits to buying green bonds, but there are also reputational risks,” says Manuel Lewin, the New York-based Head of Responsible Investment at Zurich Insurance Company, which had invested $1.2 billion in green bonds by mid-2016.

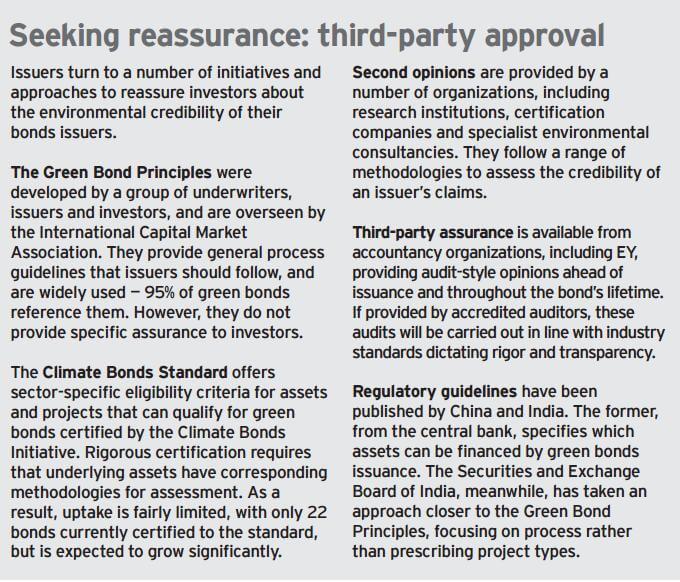

To add this sought-after integrity, the market has responded with voluntary initiatives; the Climate Bonds Initiative offers a certification program for bonds that meet its criteria. The Green Bond Principles, developed by green bond issuers, underwriters and investors, recommend transparency and disclosure by issuers, seeking to ensure the integrity of the market.

By themselves, these don’t always add the credibility to issuers, so many are now commissioning “second opinion providers” or traditional audit firms to provide a third-party assessment of each green bond they issue (see the box on page 7).

“These external stamps of approval provide crucial reassurance to bond buyers. But, ultimately, the investor needs to properly understand what it is investing in,” says Mathew Nelson, EY Asia-Pacific Climate Change and Sustainability Leader. “Investors need to know how to ask the right questions, to understand which criteria are applied to the bond, and to preferentially invest in those bonds where the criteria are properly applied and where independent assurance is provided.”

As might be expected, issuers provide plenty of information to potential investors when they are marketing green bonds, but some market participants are concerned that this disclosure should also continue over the lifetime of the bond.

“One of the concerns in the market is that once a bond has become green-labeled, it’s in the universe indefinitely,” says Stuart Kinnersley, the CEO of Affirmative Investment Management, a London-based green bond asset manager. “What we aim to do is monitor the use of proceeds afterwards, to ensure the issuer does what it says it will do.”

Nelson notes that a growing number of issuers are paying attention to these concerns, and are commissioning auditors to review how the underlying assets are performing over the life of the bond. Such reviews — conducted and published in line with the ISAE 3000 assurance standard – offer a higher degree of reassurance to investors, he believes. Another potential problem for investors is a relative lack of supply; despite recent growth, green bond issuance accounts for a tiny fraction of the overall global bond market, which is worth an estimated $100 trillion. “The main problem is getting new green bonds into the market,” says Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative.

These wind turbines are being constructed at Kenya’s Lake Turkana, supported by green bond financing.

For all the growth in issuance, sales of new green bonds are typically heavily oversubscribed; this offers a marginal pricing advantage to issuers. Rather than having to price new issues at a slight premium to entice investors, organizations selling green bonds can often price them in line with existing debt. Some research indicates that green bonds are commanding a price premium in the secondary market. According to Barclays, there is a 20 basis point spread in the yields of green bonds and comparable issues, as a result of strong demand from investors.1

The reason for this supply and demand imbalance include the additional costs involved in structuring and issuing green bonds compared to conventional debt, and the fact that the world’s capital markets are awash with liquidity, making it easy for issuers to raise funding.

Kidney also notes a relative lack of underlying green projects requiring financing, which he blames on inadequate policy support from governments. Meanwhile, on the demand side, many green bond investors either have explicit green bond mandates from their clients or have themselves publicly committed to support the market with green bond purchases, and therefore tend to buy and hold green bonds as they are issued. “The premium is still minor at this point,” says Kidney, “but if that changes, it will dampen the market.”

“If pricing goes much tighter than the regular bond, that would pose a challenge for new investors,” says Joop Hessels, head of green bonds at ABN AMRO in Amsterdam. They would be required to seek a specific mandate from their clients to pay a premium for green bonds, he says, and many would consider that to be a breach of their fiduciary responsibility to their ultimate beneficiaries.

New opportunities ahead

The relatively small size of the green bond market provides opportunities for issuers, however. “Much of the issuance to date has been from supranationals, utilities and financial issuers. This raises concentration risk,” says Hendrik Tuch, head of rates at Aegon Asset Management, an arm of the Dutch financial services group.

He also notes that most green bonds are at the high end of the credit spectrum, and are relatively short-dated, while many of his institutional clients favor longerdated paper that better matches their liabilities.

This opens the market to new forms of bond issuance against green asset classes that tend to favor longer tenure of debt, such as more sustainable forms of transport and infrastructure. Other analysts note that what is sometimes referred to as the “labeled” green bond market — i.e., those bonds where the issuer explicitly describes its bond as green — is only a subset of those bonds issued to finance environmentally friendly assets.

The Climate Bonds Initiative and HSBC track what they describe as “climate-aligned” bonds. They have identified a universe of $694 billion of bonds, two-thirds of which are issued by entities in the transportation sector. China Railway Corporation, for example, has issued $194 billion in bonds to finance the expansion of China’s high-speed rail network. Investors also need to be aware that while underlying assets may meet “green” criteria, the bond proceeds are often used for refinancing, rather than for underwriting new assets.

This can raise a concern for some about the “additionality” of the green bond market; is this simply a rebadging of financial flows that would have happened anyway? “A profound problem with the green bond market is the lack of additionality,” says Steve Waygood, Chief Responsible Investment Officer at London-based Aviva Investors, the asset management of the financial services firm. “Where is the new green infrastructure and renewable kit that has been financed with green bonds?

Both investors and policymakers need to be aware that the vast majority is repackaging and refinancing existing projects.” While this is true, Kidney is unconcerned, and says: “Bonds are not a project financing tool. What you use the bond market for is refinancing,” freeing up space on corporate balance sheets to allow new projects to be developed.

What Kidney is more concerned about is governments stepping forward to bring new projects forward that they can then finance with green bonds. Nelson has a more profound argument against those demanding that projects funded by green bonds be additional. “It isn’t the responsibility of the green bond market to push down emissions — that’s the responsibility of government policy,” he says. “The reason people should be investing in green bonds is because they see their potential for more attractive risk-adjusted returns over other debt instruments because the underlying assets will perform better in a low-carbon economy.

“The fundamentals of the green bond market are about financial return — otherwise, the danger is the market becomes part of the corporate responsibility agenda.”

Filed Under: Financing, News