By Keith Martin, Co-Head of Projects, United States, Norton Rose Fulbright

The Internal Revenue Service said that developers will have four years to complete a new wind farm or other renewable energy project and qualify for federal tax credits without having to prove that the construction work was continuous.

The four years will be measured from the end of the year in which construction starts on the project.

For example, if construction of a new wind farm started in 2013, then the project must be completed by the end of 2017.

If it takes longer, then the developer will have to prove that work after 2013 was continuous.

The IRS made the statement in the first of two new notices expected after Congress extended the deadlines to start construction of new renewable energy projects to qualify for tax credits.

A second notice is expected later and will focus on solar issues.

The first notice is focused mainly on wind, geothermal, biomass, landfill gas, incremental hydroelectric and ocean energy projects.

It is Notice 2016-31. The full text can be found here.

Developers of such projects must have the projects under construction by December 2016 to qualify for full tax credits.

Wind developers who start construction of their projects in any of the next three years after 2016 can qualify for tax credits at reduced levels. The levels are 80% for wind farms starting construction in 2017, 60% in 2018 and 40% in 2019.

There is no phase down of tax credits for geothermal, biomass, landfill gas, incremental hydroelectric or ocean energy projects. They must be under construction by December 2016 or they will not qualify for any tax credits, with one exception. Geothermal projects qualify for a permanent 10% investment tax credit no matter when work on the project is started.

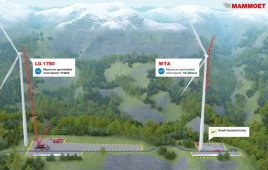

The tax credit extension also opens a short window of opportunity for turbine manufacturers to make a vigorous push to upgrade turbines at older US wind farms.

There are two ways to start construction of a project.

One is by starting physical work of a significant nature. There is no fixed minimum quantity or dollar amount of work required to be considered “significant.” The IRS looks at the task. For an analysis of how much work is required and on what tasks, see Additional Construction-Start Guidance. The new notice gives examples of tasks that are considered significant at different types of projects: wind farms, hydropower facilities, biomass and trash facilities and geothermal projects.

The other way to start construction is by “incurring” at least 5% of the eligible project cost by the deadline. Costs are not incurred merely by spending money. They only count once equipment or services are delivered, with one exception. A developer who pays for equipment at year end and takes delivery within 3 1/2 months after the payment can count the payment as incurred on the payment date. Delivery can be at the factory.

It is not enough merely to start construction. There must also be continuous work on the project after construction starts. Until now, the IRS has not made developers prove continuous work as long as the project is completed within two years after the construction-start deadline.

New rules

The new notice takes a different approach.

Counsel will have to determine when construction of a project started. That sets a four-year clock running starting at the end of the year in which construction started. Thus, for example, if construction started in 2013, then the project must be completed by December 2017 or else the developer will have to prove continuous work.

Projects that were under construction on account of significant physical work and then run past the four-year mark to be completed must prove “continuous construction.” This may be impossible to do for many projects.

Projects that were under construction on account of the 5% test and then run past the four-year mark must prove “continuous efforts.” This is easier to do because development-type tasks qualify as part of the continuous efforts.

It is always a good idea to keep detailed records of what is being done on the project in case construction takes longer than expected. For practical lessons from the last two rushes to start construction, see Another Race to Start Construction: Practical Advice.

The IRS repeated in the new notice that “preliminary activities” do not qualify as significant physical work. Examples of preliminary activities are securing financing, obtaining permits or doing test drilling at a geothermal site.

There can be a break in construction due to events outside the developer’s control. The IRS had given nine examples earlier of things that are considered outside the developer’s control. The new notice adds two more. The earlier list said that financing delays of “less than six months” can be excused. The new notice says simply “financing delays” without setting a time limit. The new notice adds “interconnection-related delays.” Many developers had asked in the past whether they can work backwards a year, for example, from when the utility will be ready to interconnect a project to start work in earnest on the site.

The new notice addresses three other issues.

First, the IRS said a developer who relied on physical work to start construction ― say in 2015 ― cannot now incur at least 5% of the costs in 2016 to buy more time to complete the project without having to prove continuous work.

Second, the agency is taking a more relaxed view of what happens if construction extends beyond the four-year mark. At worst if the developer cannot prove continuous work on the project, only the wind turbines that took more than four years to get into service will be denied tax credits. The rest of the project will qualify for tax credits without having to prove continuous work.

Finally, the notice addresses how to determine whether new tax credits can be claimed when wind turbines are repowered or retrofitted.

The tax credit extension opens a short window of opportunity for turbine manufacturers to make a vigorous push to upgrade turbines at older US wind farms.

In general, the owner must spend at least four times on the repowering the value of the equipment that the owner retains from the original project in order for the repowered turbines to qualify for new tax credits. This test is applied on a turbine-by-turbine basis, meaning that each turbine, pad and tower is considered a separate facility. Thus, if $300,000 in equipment value is retained from the original turbine, pad and tower, then at least $1.2 million must be spent on the upgrade to claim another 10 years of production tax credits on the electricity output or an investment tax credit on the new spending.

Construction of the repowering must start by the deadline to qualify for tax credits.

The 5% test requires incurring only 5% of the new spending, not the total project value.

The new notice gives the following example of how these rules work in practice. Suppose there is an existing wind farm with 13 turbines. Each of the turbines is more than 10 years old. The developer retrofits 11 of the 13 turbines and spends $1.4 million per “facility” ― turbine, pad and tower ― on the retrofits. It retains used components with a value of $300,000 at each facility. Thus, the new spending is more than four times the retained equipment value. The total spending on all 11 retrofits is $15.4 million.

The developer treats the 11 retrofitted turbines as a single project with a total cost of $15.4 million.

Therefore, if the developer incurs at least $770,000 in costs by the deadline, then it will be considered to have started construction on the full repowering (5% x $15.4 million = $770,000). It does not have to show at least 5% in incurred costs for each individual turbine. Additional tax credits cannot be claimed on the two turbines not repowered.

Filed Under: Construction, Financing, News