By Cherise Gaffney, Tim Taylor & Chad Marriott

Partners, Stoel Rives LLP

. In 2018, policymakers set a goal of 100% clean energy in California by 2045. One way to meet or beat that timeline? Offshore wind. An American Jobs Project report finds that offshore wind industry could support over 17,500 jobs in 2045, however, developers will first have to abide by state and federal regulations for permitting and construction.

Offshore wind projects are extremely capital intensive, so it makes sense that the first wave of development in the U.S. has focused on high-load, transmission-constrained East Coast regions. New England is one excellent example, where power prices are high enough to support offshore wind.

The relatively shallow water depths — which extend beyond state territorial waters and submarine topography off the Atlantic coast — complement existing and well-proven wind-turbine installation methods.

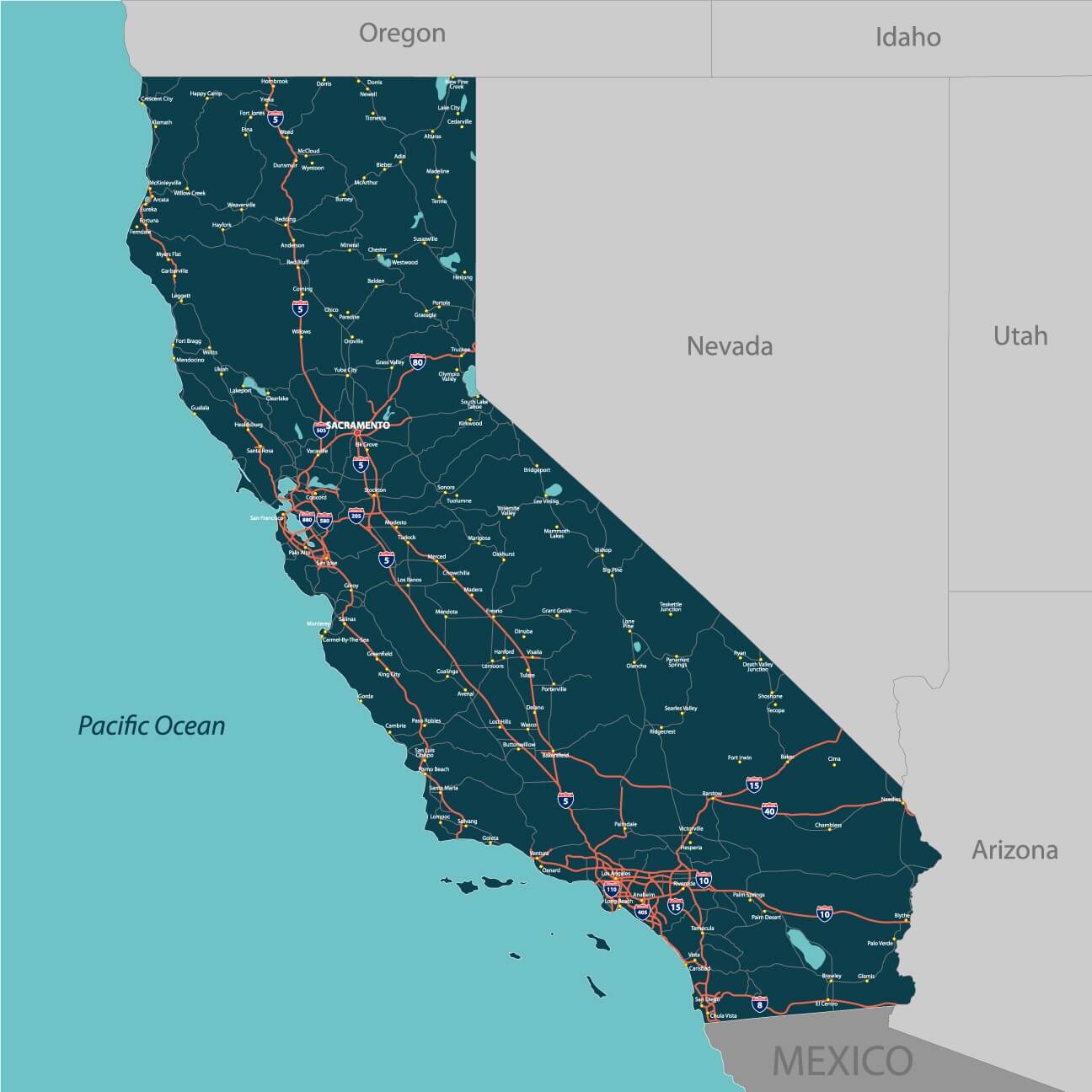

But make no mistake, California is the natural target for the second wave of development. As the world’s fifth-largest economy with a power-hungry population, an extensive coastline, and a progressive legislature and governor, California is likely to lead the offshore wind industry on the West Coast.

Regulations, permitting, and financial considerations may offer new challenges to offshore wind developers out west.

Regulation & permitting

Attaining approvals for offshore wind projects in California will involve several federal and state agencies that are charged with managing and protecting:

Submerged lands and coastal resources

- Protected species

- Cultural resources

- Water quality

- Existing ocean uses, such as crabbing and fishing

- Shipping and navigation

- Recreation and public safety

Developers considering offshore wind projects in California will need to approach the federal and state permitting process strategically. This requires an in-depth consideration and understanding of how potential resource impacts and regulatory approvals and conditions may affect project planning, development, and timing.

Wind developers will also need to consider federal and state approvals.

Federal approvals

For successful offshore wind development, it will be important to work closely with several federal agencies.

With offshore wind development on the U.S. East Coast well underway, California is likely next in line for wind energy projects in the Pacific.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has jurisdiction over renewable projects that are located on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS), the area three nautical miles from California’s coast. BOEM is responsible for granting leases, easements, and rights-of-way for renewable energy development activities, including the siting and construction of offshore wind projects on the OCS. It offers a competitive leasing program, which includes a lease sale auction.

How it works: The winner of the lease submits a site assessment plan for BOEM’s approval, allowing for resource assessment and technology testing. The leaseholder then develops a construction and operations plan for BOEM’s approval.

In addition, the BOEM has a number of other responsibilities, including evaluating the proposed project pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), assessing the potential impact of its approvals on properties under the National Historic Preservation Act, and consulting with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The latter is important to confirm that the construction and operation of the project are unlikely to jeopardize listed species or destroy or adversely modify critical habitat.

Other federal agency approvals will also be required, depending on the project. Specifically, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approval under section 404 of the Clean Water Act will be needed for any dredge or fill approval, including trenching for offshore cables or wetland fill that may be associated with onshore facilities. Authorizations under the Marine Mammal Protection Act from NMFS may also be necessary.

Additionally, a U.S. Coast Guard Private Aid to Navigation Permit will be required to ensure compliance with private and uniform aid marking requirements and to ensure waterway safety.

State approvals

Several California agencies are likely to be involved in offshore wind development along the state’s 840-mile coast. Under the California Coastal Act, the Coastal Commission has jurisdiction over the “environmental and human-based resources of the California coast and ocean … for use by current and future generations.” (Source: Pub. Resources Code §30001.5)

The Coastal Commission regulates the development within the coastal zone (defined as offshore to the state’s jurisdictional boundaries and variable distances inland — sometimes by as much as five miles) and affected local coastal communities. As with other offshore energy development industries, offshore wind is subject to the Coastal Commission’s authority to determine consistency with the Coastal Act.

The State Lands Commission is responsible for development and other operations over submerged public trust lands in the state. Typically, its jurisdiction is accountable for in-water projects, such as docks and marinas, but approvals will also be required for onshore cables from offshore wind turbines that cross the shoreline. These facilities are subject to discretionary permitting in the form of fixed-term leases issued by the Coastal Commission and conditions to protect public access, including coastal access and the natural environment.

The California Department of Fish & Wildlife administers the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) and will be called upon to determine whether any part of an offshore wind project affects threatened or endangered species or their habitat. Proponents are wise to understand the intricacies of CESA, including how it differs from the federal ESA, and whether incidental take permits are required for state-listed species.

Offshore wind energy developers will require a strategic approach to successfully meet the federal and state permitting processes. This means a clear understanding of how a project may impact coastal resources and marine life.

Finally, local agencies may have a hand in offshore development either through focused planning tools, such as Local Coastal Programs, or other onshore local permitting and approval processes. The 76 coastal California counties and cities vary widely and warrant close individual scrutiny depending on a project’s location.

Discretionary actions by public agencies in California that may have a significant physical effect on the environment are subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Wind developers must consider the time and cost implications of compliance with this far-reaching statute. CEQA mandates public notice and participation and, when relevant, the mitigation or avoidance of potentially significant impacts.

With the exception of the Coastal Commission, which is subject to an equivalent CEQA process known as a Certified Regulatory Program, each of the agencies identified must fully comply with CEQA before approving a project.

Financial considerations

As the wind industry learns best practices for permitting offshore projects, individual companies will develop their own thesis for financing them.

With a relatively long timetable for offshore wind in California and a steep learning curve, the financing landscape is likely to change over time. Large balance sheet sponsors are expected to continue to dominate the field, but the overall capital stack may look somewhat different in the next five to 10 years.

For example, the production tax credit (PTC) and the investment tax credit (ITC) will have expired — possibly, without renewal. For now, the safe assumption is that California offshore wind will be unable to rely on the same federal tax credits that have accounted for a substantial portion (typically 40 to 50%) of terrestrial wind financing. If they are, it’s unclear whether the credits would represent a comparable percentage of the capital stack.

Without the PTC or ITC, the gap fillers will likely be term debt and equity partnerships akin to some of the recently announced joint ventures, such as Engie-EDP and EnBW North America-Trident Winds.

Filed Under: Featured, News, Offshore wind, Policy