The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC) Rule 1000 is a good first step toward a coherent, long-distance transmission policy. This Rule, enacted in July 2011, usurps utilities’ right of first refusal to disallow transmission lines from being built on their territory, and orders utilities to work with others outside of their control areas to develop plans and transmission systems that should reduce costs to consumers. FERC concludes that incumbent transmission providers’ ability to use their “first refusal” in their own economic self-interest may discourage new entrants from proposing new transmission projects in the regional transmission planning process. The Rule also proposes to reform cost allocation to aid in the development of renewable energy.

FERC’s Rule 1000 attempts to open discussion of transmission-line development over a larger regional and inter regional area, and to a larger audience including merchant-transmission developers and independent power producers.

FERC’s Rule 1000 attempts to open the discussion of transmission line development over a larger regional and inter regional area, and to a larger audience including merchant transmission developers and independent power producers—which I call “Green Lines.”

FERC justifies changes to these rules by using the “just and reasonable rates and undue discrimination by public utility transmission providers” clause which includes the removal of right of first refusal from utilities in the decision to construct transmission facilities.

This opens the discussion of transmission planning to additional parties involved in the transmission planning process. No longer do regional utilities that serve load have a monopoly on siting transmission, but merchant transmission and independent power producers may now participate in discussions and provide alternative solutions. In its ruling, FERC justified the rule change using the utilities’ economic self-interest in seeing certain transmission lines and systems installed.

To determine whether FERC Rule 1000 will be like other (unsuccessful) federal government attempts to get green power to market, or whether it will turn out to be the key that sets in motion a cascade of effects that makes this possible, it helps to understand some background of long-distance Green Line transmission.

A new, New Deal?

Some 80 years ago, the Depression-era New Deal drove energy initiatives such as the Tennessee Valley Authority dams, Niagara Falls, the Hoover Dam, and the Grand Coulee Dam. These projects were successful for a variety of reasons, not all of which are found in today’s green power projects.

With a driving need to stimulate the economy in the 1930s Depression, there was a national willingness to spend public money and buy bonds in order to create jobs. These hydroelectric projects delivered regulated power, whose output was easily increased or decreased to meet load. The power was also reliable, due to the large reservoirs behind the dams. Because generation was low cost, transmission line capacity factors exceeded 70%, which justified the economics for the long distance they traveled. Demand for power was within the same regional authority, which simplified contracting sales, i.e. power generated in Niagara Falls was sold to New York; Grand Coulee was sold within the Bonneville Power Administration; Hoover Dam to Los Angles.

The federal government had eminent domain to acquire property, and low-cost bonds to finance these projects. The result was a resounding success, in the production of reliable, low-cost electricity that soon sparked industries generating jobs in the Pacific Northwest, California, upstate New York, and the eastern seaboard.

Today’s green power producers face significant challenges not encountered by the 1930s projects—perhaps calling for significant changes in how power transmission projects are paid for. It could be that FERC hopes its Rule 1000 will be a catalyst for that change.

Perhaps the greatest barrier is that just about any green-power source seems by destiny to be in areas without substantial markets. Windy states such as Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas are generation-rich and demand-poor, without substantial populations, or much energy-dependent industry. Places with substantial, reliable solar resources such as Nevada and New Mexico likewise have slim populations. And areas that still have developable hydro resources, such as northern Quebec, are also low on demand.

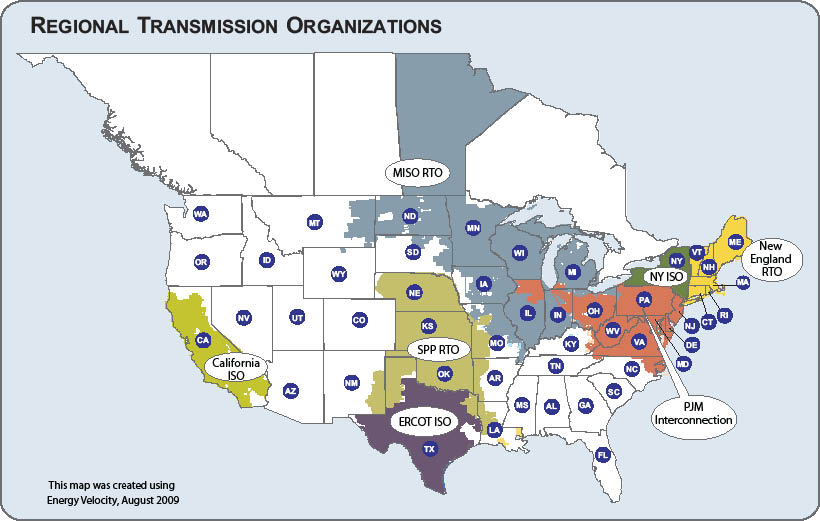

Therefore, any transmission lines connecting load must be long. This means substantial power loss, the need to negotiate significant rights-of-way, high construction costs and at least until FERC Rule 1000, difficulties in crossing regional territories. Power generated in Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, which makes up a large part of the Southwest Power Pool (SPP), must be carried west through Arizona and New Mexico to California, or east to the Southeast, Florida, and the Mid-Atlantic States.

Rule 1000 asks each Regional Transmission Organization (RTO) region to develop a methodology to define how each area benefits from a specific interregional interconnection. Based on the relative benefit, each region is to pay its proportional share of the cost for the transmission line. This sounds simple, but what is the benefit realized, for example, by PJM for interconnecting with the SPP RTO to import green energy when it could just as easily get offshore wind power?

A widely used reference for the price of electricity in PJM is the “Western Hub.” In order to be “Just and Reasonable,” I believe the generator in the SPP RTO region must be able to generate the power in Kansas and deliver it to PJM’s Western Hub at the Western Hub price. The price at the Western Hub is determined, largely by the price of natural gas. Therefore, the producers of electricity in SPP, NYISO, ISO-NE or FPL must be able to generate and deliver it to the Western Hub for less than the cost of shipping natural gas and using it to generate power at the Western Hub.

Restating Rule 1000’s question would then be, what is the benefit of burning natural gas and making the electricity within the RTO in which it is used, versus using electricity created outside the region? What benefit is realized by the region in which the electricity is used and what is the benefit to the region in which it is generated?

In addition to the immediate economic issues, political issues will also need to be resolved to install these transmission lines. Political and business leaders of some coal-producing states such as Ohio, West Virginia, and Virginia can be expected to fight hard against power from competing sources crossing their territory.

Essentially, today’s green power sources are an inverse of the situation faced by the FDR-era hydroelectric planners: much of green power is created in one region and must be sold in another. In addition, transmission lines face high regulatory and permitting hurdles and potentially low capacity factors that do not justify the economics.

Perhaps most significantly, the capacity factors for much of the Midwest wind energy is expected to be around 30 to 40% – much too low to economically justify long-distance transmission in itself.

A recent conversation with a Kansas-based wind power producer told me that the main challenge lies in finding markets for the power in high-demand places outside the immediate region. The situation is typical in that if the market for green power can be developed–if a utility in a high-demand area such as Florida signs a power purchase agreement with this Kansas producer–the transmission problem is on its way to a solution. But currently, local planned generation exceeds local load, and it also exceeds the transmission capacity to export it outside of the local area.

The 1930s hydro projects succeeded because the right elements were in place. What elements need to be present for that Kansas power producer to reach markets in Florida or power producers in Maine to reach markets in Connecticut—and for the larger shift towards green power to take place? Some elements are already available.

Renewable generation technology, particularly for wind, is maturing. Transmission technology also shows improvement, including greater efficiency of high voltage dc lines that are efficient and become economically justifiable over long distances.

We see examples of across-the-utility-boundary cooperation, such as Hydro Quebec’s existing transmission ties with New England, or PJM and NY-ISO ties between New York and New Jersey. In these cases the generators sell power at US market rates, which are high enough to subsidize local consumer rates. If SPP generators can do the same for less than the cost at the Western Hub, then these same generators will have the ability to reduce rates for local consumers, resulting in benefits for both ends of the line.

The development and economic production and operation of energy storage will of course resolve green line capacity-factor issues. Until then, the synergies of wind and solar could be used to increase capacity factors. Interspersing solar arrays in with wind turbines, to use the same transmission interconnection equipment, is one way this can take place. The wind tends to blow more lightly on hot, sunny days when solar collection is at its most efficient. During the night when solar generation is off, wind production is at its peak.

This can go further, through taking advantage of a fortunate aspect of North American geography: in many cases, the pipelines carrying gas to market cross or run close to areas of wind and solar resources. Locating gas turbines on areas of wind and solar generation, to help balance the electricity production curve, can go a long way to boosting low capacity factors.

Through the installation of new gas fired turbines, Independent Power Producers may be able to earn carbon credits if they can provide greener energy that produces reliable power at a low cost, which could enable the shut-down of coal-fired installations.

In the end, the economic case must be made for transmitting energy from one region to another, which means generation costs must decline and capacity factors for green lines need to rise. FERC Rule 1000 has set in motion a process that will help provide green energy to more densely populated areas and it has helped open the discussion of energy created by a wind turbine in the Midwest to help recharge a cell phone in New Jersey. But in helping to prepare a good regulatory and fiscal environment, this Rule may be the first step along that journey. WPE

By: Charles Vansant, PE, Senior Consultant, Electric Power Systems, Golder Associates, www.golder.com

Filed Under: Policy