History can offer hindsight and wisdom to present-day circumstances. The slow, but sure-moving U.S. offshore wind industry is one example. Although much of the sector is looking to Europe and the UK for experience and lessons learned, we can also look in our own backyard. Case in point: Cape Wind.

Remember the controversial project, which after a 16-year battle for developmental approval in Nantucket Sound, surrendered its federal lease area at the end of 2017? The proposal had a good run, and its eventual failure was certainly not for lack of effort.

In December 2017, Cape Wind Associates officially announced an end to the development of its proposed offshore wind farm and surrendered its federal lease for 46 square miles in Nantucket Sound — officially putting an end to a 16-year effort to build the controversial project.

Lauren Glickman, who works as a clean energy communications consultant — including with WRISE, the Women of Renewable Industries & Sustainable Energy — recalls directing a grassroots campaign in support of Cape Wind. “Working on a grassroots campaign in support of Cape Wind was a pivotal moment for me,” she shares. “It was an opportunity to work on a solution-oriented campaign for clean energy instead of just fighting against the fossil-fuel industry.”

However, opponents argued that the project posed a threat to offshore navigation, marine life, birds, and the local economy. After multiple permitting and litigation losses and delays, and state regulatory denials, the project proved impossible.

“Cape Wind introduced to me to how critically important communications and community outreach can be in the success or failure of a project. It is not enough to offer a clean energy alternative,” says Glickman. “Stakeholder engagement is also crucial.”

The final barriers to the project first came in January 2015, when energy providers Eversource and the National Grid opted out by ending contracts to buy power from the proposed wind turbines. Then, in 2016, matters turned worse when the state Energy Facilities Siting Board declined to extend permits for the project that had originally been issued in 2009.

Although, in hindsight, Cape Wind seemed doomed to fail from its early planning stages, it failed to deter offshore wind efforts in the country. America’s first and only, five-turbine, 30-MW Block Island Wind Farm off the shores of Rhode Island is one small but positive example of the offshore sector’s determination. As the proposal for Cape Wind was losing its battle, Block Island successfully began construction and operation.

“Even though Cape Wind may not have become a reality, it paved the way for projects like Block Island Wind and the growing interest in scaling the U.S. offshore wind industry in the Northeast and beyond,” says Glickman.

Cape Wind also led to key insights and new approaches to offshore siting. Just ask Hilary Tompkins, a partner with the law firm Hogan Lovells, in Washington, D.C. Before this, she spent nearly eight years as the Solicitor for the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), under the Obama administration. The DOI is responsible for the management and conservation of public lands, and natural and wildlife resource programs.

Tompkins’ DOI legal team inherited Cape Wind from the Army Corps of Engineers. Although an application for the project had been filed in 2001, it was still going through the Environmental Review Process in 2009.

“The project serves as an unfortunate example of government bureaucratic delays, but you have to remember that we were just developing renewable energy regulations at the time,” she shares. “So, there was plenty to learn.”

Here are three of those lessons.

1. Location matters

“It’s extremely important to set a project in the ‘right’ area with low conflicts,” says Tompkins. For example, one opposition group filed more than 25 appeals to obstruct the construction of Cape Wind. Although the project eventually prevailed in legal appeals, there were other permitting snags.

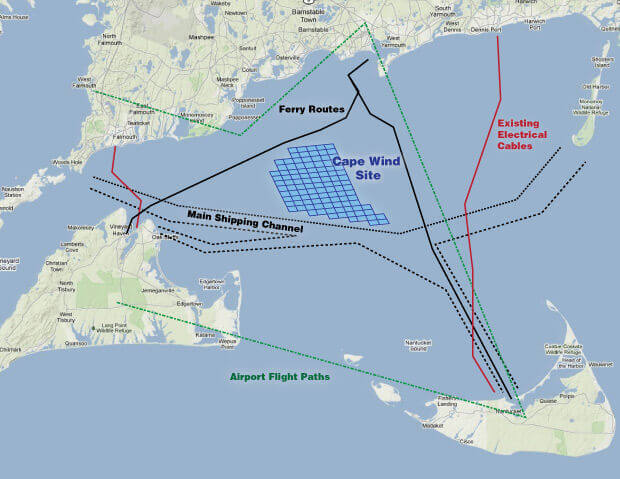

The Cape Wind farm would have gone here.

“Siting was a key issue,” she explains. “Ideally, developers should avoid marine transportation areas such as travel routes, where fisheries are significantly active, and where there might be Federal Aviation Administration concerns with air travel. They must also consider sea-life migration pathways and endangered species — and avoid national historical sites.”

The National Park Service had also ruled that Nantucket Sound (where Cape Wind was sited) fit eligibility criteria for listing on the National Register of Historic Places because of its significance to two Native American tribes.

Fortunately, awareness has led to progress. “After Cape Wind, the Interior got much better at identifying those areas in the Atlantic that are suitable for offshore wind. So, I believe the regime we’re currently operating under is more informed and educated about minimizing the impacts that could lead to conflict and permitting delays,” says Tompkins.

Consider the record-breaking auction held by the DOI’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in December 2018, which included nearly 390,000 acres offshore Massachusetts. Eleven wind companies participated, with a $405 million winning bid from Equinor, Mayflower Wind Energy (a joint venture between Royal Dutch Shell and EDP Renewables), and Vineyard Wind.

The winning bids for the Massachusetts lease areas far exceeded the previous record bid for a single lease area, set by a $42.5 million bid from Equinor (then Statoil) in a 2016 New York lease auction. The government is better managing siting areas and supporting the growth and economic development of the offshore wind industry.

“This is an outgrowth of efforts from Cape Wind, which I think is very encouraging and I’m optimistic that this time, developers are going to have greater success in the offshore industry,” she adds.

2. Avoid litigation

One caveat to Tompkins’ last statement is this: “Developers must consider all of the various legal review requirements that come from different directions when siting and constructing wind projects,” she says. “Because you want to avoid litigation at all costs.”

Tompkins speaks from experience. Cape Wind faced numerous legal battles, including challenges that its turbines would present hazards to flying aircraft, migrating birds, marine life, and the fishing industry.

“It is critical to find ways to streamline the approvals process for a project in a way that will be legally defensible,” she says. This means knowing who to ask for what. “For instance, we got dinged for Cape Wind because we relied on BOEM to address certain environmental impact issues, such as with migratory birds. However, the court told us we were wrong and, instead, should have relied on the Fish and Wildlife Service to attain the correct information.”

Tompkins says the DOI has since focused on developing new approaches, including digitalization of data to better streamline the environmental review process. The aim is to obtain and secure reliable information and a faster permitting process. “I think the Interior should also create a universal environmental policy approach for required documentation and work with contractors who already know the leasing area to further streamline that review process,” she says.

One example is BOEM’s draft guidelines for the use of a “design envelope” approach in construction and operations plans (COPs) for U.S. offshore wind projects, which is standard in some European countries. The design envelope approach lets the BOEM analyze the environmental impacts of a proposed project, while reducing or eliminating subsequent environmental and technical reviews, without sacrificing environmental safeguards.

According to the BOEM, this approach would save permitting time and “afford developers a degree of flexibility and allow them to make certain project-design decisions — such as which turbines to use — at the more commercially advantageous time later in the project development process.”

Nonetheless, Tompkins says it’s imperative to cross all “i’s” and dot all “t’s.” Offshore projects require multiple federal agency approvals — think the National Historic Preservation Act, Endangered Species Act, NOAA Fisheries reviews, and others — and it’s relatively easy to miss a step. “Even after the site assessment is approved, developer’s move into the construction phase of a project and that’s a much more formidable undertaking when major environmental reviews come into play under NEPA.”

NEPA, or the National Environmental Policy Act, process occurs when there is a proposal to take a major federal action — such as an offshore wind project in federal waters. These actions are defined at 40 CFR 1508.18 and the environmental review under NEPA can involve three different levels of analysis. (Learn more here).

One benefit from Cape Wind is the framework used by the DOI for offshore wind permitting, which involves a four-phased leasing process (lease sale, site assessment plan, construction and operations plan, and decommissioning) that requires more significant environmental review at the construction phase of a project as opposed to burdensome environmental reviews at every stage.

“It’s so good to know this process is defensible and was recently upheld by a federal district court in Washington, D.C., in the Fisheries Survival Fund v. Jewell case,” said Tompkins. This case involved the wind lease that the DOI issued to Statoil Wind US in offshore New York.

3. Plan ahead

“I may sound biased but it’s critical to have legal counsel, who have worked in the private and public sector, understands your business, and the government approval process,” says Tompkins. “These are examples of processes that developers should think about and map out on the front-end of their project, so they know what to anticipate down the road.”

She says there’s a lot to consider with offshore wind, aside from the project itself. For example, port infrastructure, which must be able to accommodate turbine components and crew transfer. Then, there’s the transmission grid considerations.

“We also need a transmission grid that can receive this new source of energy from offshore and deliver it efficiently and cost-effectively onshore. In North Carolina, we’re even seeing the state assess who will have transmission authority over this sector,” adds Tompkins. “And really, all participating states will need to figure out how domestic energy sources will best include and outsource offshore wind.”

This means offshore developers will need to work with governments and state officials at multiple levels for permitting, construction, and transmission. “There’s going to be an evolution in our energy delivery system,” says Tompkins. “Getting those who were involved from the early days and development of the offshore industry, and from inside the government, is an important key to long-term success.”

Filed Under: Featured, Offshore wind

Dear Michelle Froese, Thanks for your document, lesson learned from Cape Wind. I happen to participate in the Offshore Wind Conference in Baltimore some time ago when I was the Chairman of Korea Wind Industry Association. I noticed that more than 5,000 participants clouded and I suspected that there is no offshore wind project in the USA sea water even Cape Wind announced the very attractive Tariff made in early stage of offshore industry. While UK and EU made a good progress and they participate in the conference to sell their experience and know-how. Now I am intend to participate in the HKS Climate Change, Economics and Policy course. I intend to suggest NZE 2050 which will benefit to deploying the offshore wind farm project. USA intend to add 22GW by 2030 and 86GW by 2050 while Republic of Korea intend to promote 32GW by 2050 which are in the project pipeline. With best regards,

Rimtaig Lee