Should construction companies in the wind industry design components to an accepted specification or “fit for purpose”? A landmark ruling by the UK Supreme Court has shifted the legal landscape surrounding offshore wind farm design and construction, which presents the industry with a new paradigm in dispute claims.

Lorne Gifford / Civil Engineer / Brookes Bell Group

Grant Greatrex / Managing Partner / ELAN Forensic

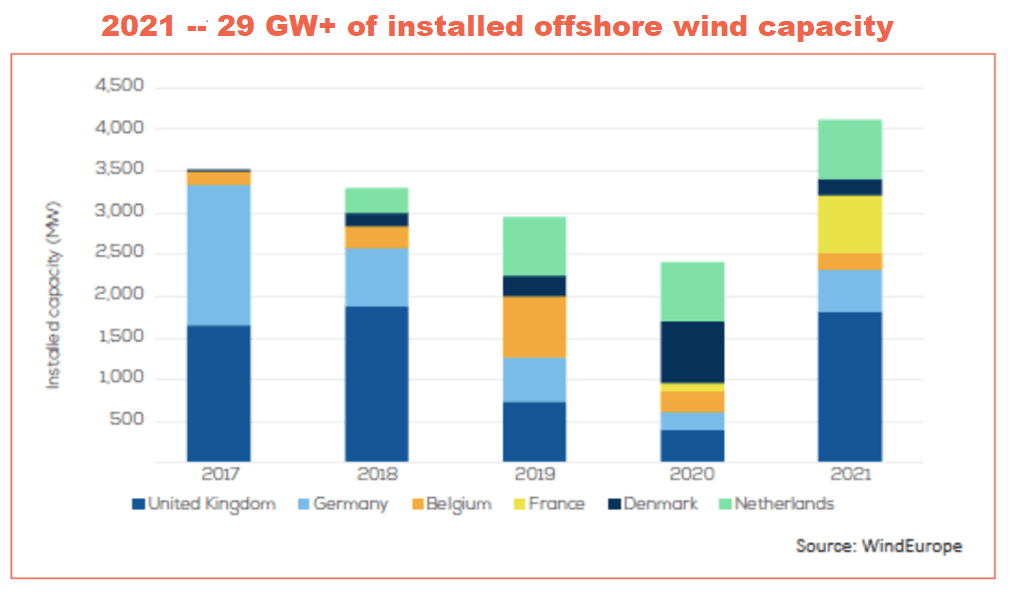

Offshore wind has evolved from alternative energy to a primary one with an essential role in the global energy transition. The installed capacity of offshore wind will increase thanks to recent cost reductions that provide a strong economic case for investing in this growing industry. However, significant challenges must be overcome before the offshore wind industry can thrive

One challenge wind developers face is in offshore construction. The components that make up an offshore wind farm (OWF) are typically larger than for onshore projects. OWFs are also being sited in deeper waters and further offshore. With regards to design, construction, and operation, OWF asset owners, operators, and contractors must navigate a changing legal landscape, exemplified most notably in a landmark judgment passed last year in the UK’s Supreme Court.

The case and the judgment

In August 2017, the Supreme Court handed down judgment in the high-profile case of MT Højgaard v. E.ON Climate & Renewables. The case concerned the foundation structures of two OWFs, Robin Rigg in the Solway Firth, which were designed and installed by MT Højgaard. The foundations failed shortly after project completion because of grouted connection problems, which also occurred at other offshore projects. The failures came from a fundamental fault in the industry’s standard design code (DNV-OS-J101) that E.ON had specified for use.

Current installed OWF capacity in Europe (12.6 GW) is set to more than double in the next five years with an additional 16.3 GW added to the OWF network. The UK will maintain the lead in total OWF installed capacity.

The legal dispute concerned who should bear the remedial costs in the sum of €26.25 million. After hearings in the Technology and Construction Court and the Court of Appeal, the final judgment of the Supreme Court concluded that MT Højgaard was contractually responsible for the problem because it failed to deliver foundations that were fit for their purpose.

This judgment sets a precedence of responsibility on suppliers and contractors that their work is “fit-for-purpose,” even where clients have specified the use of a standard that proves to be flawed. [In April 2016 DNV withdrew OS-J101, which was the standard when the building was completed in 2010, and replaced it with DNVGL-ST-0126, noting that ‘This document has been totally revised’.] The consequences of this ruling for suppliers and developers in the offshore wind industry is significant and will affect future project contracts for design and management.

Drivers of disputes

The case of MT Højgaard versus E.ON Climate & Renewables is just one example of an increasing number of offshore wind disputes relating to project development, design, construction, and contract management. As the table Current landscape of legal dispute shows, these disputes reflect the current stage of industry maturity in offshore renewables.

In terms of risks and disputes, a recent study by GCube revealed that more than 40% of the total number of OWF insurance claims relate to cables, 15% to foundations, 13% to electrical issues, 7% to both collision and assembly, with blades, lightning, and fire making up the remainder. According to Genillard & Co, since 2010 there have been over 10 claims per year regarding these claims, with about 100 days of downtime per incident and a cost of over €350 million to the industry.

In terms of risks and disputes, a recent study by GCube revealed that more than 40% of the total number of OWF insurance claims relate to cables, 15% to foundations, 13% to electrical issues, 7% to both collision and assembly, with blades, lightning, and fire making up the remainder. According to Genillard & Co, since 2010 there have been over 10 claims per year regarding these claims, with about 100 days of downtime per incident and a cost of over €350 million to the industry.

It is estimated that 95% of OWF construction projects have experienced cable claims with the average cost of a claim around €2.5 million. Inter-array cable damage can vary from €1.4 million to €2.4 million, while export cable damage can cost from €8 million up to €27.5 million. Support vessel costs on larger projects can cost more than €300,000 per day.

Subsea interconnectors, which transfer electricity from one country to another, also pose construction risks. UK interconnectors today total 600 km. By 2023, the figure is expected to rise to 5,500 km. During concept and early development, risks may include the site and landfall locations, routes, technology, and external threats such as collision impacts from shipping and trailing anchors. At this stage, risks can be misjudged due to a high reliance on opinion, imperfect industry practices, a failure to heed past lessons, and an intuitive dismissal of low probability risks.

Additional risks come from a poor understanding of subsea geology, which may impact measurements or equipment performance. For example, a vessel’s position and control during underwater cable lay is critical. A loss of tension control or poor accuracy while transitioning between geologies may result in cable damage. Similarly, the measurement of thermal conductivity as well as sediment movements may lead to the cable overheating during operation or becoming exposed and at risk from fishing activities.

Future claims

The offshore wind industry is developing rapidly. New turbine classes of 8 MW-plus and floating platforms for deep-sea OWF mean there are new technical challenges facing future project developers. These challenges include:

- Technology, such as floating platforms and increasing structural loads

- Topography, such as distance to shore and zoning conflicts

- Construction, including design innovation, joint ventures, and cost reduction

- Contracting, including multi-contracting, risk management, and supply-chain management

It is likely that a broad range of disputes will occur as offshore wind developers’ deal with the impacts of a harsh operating climate on project performance, turbine durability, and asset management. Design and construction flaws initially unapparent during construction or wind-farm commissioning may impact the integrity, safety, and performance of offshore wind farms as the number of cumulative operating hours increase. These may require costly remedial action.

One of the greatest threats to asset design life will be corrosion. Marine environments (salt water) contain aggressive species such as chlorides (Cl-) and will attack unprotect steels in the form of pitting corrosion. This can lead to catastrophic failure mechanisms such as fatigue. Supply condition for structural steel or bolting, in particular, is important as excessive material hardness can lead to failure by mechanisms such because hydrogen embrittlement and hydrogen induced cracking (HIC). This type of cracking can lead to unexpected catastrophic failure. Significant secondary damage to the turbine also a concern.

Mitigating claims, risks, and costs

OWF owners, operators, and contractors must prepare for potential litigation threats, or lay sound foundations for potential legal action that may arise during project execution or after commissioning. One way to do so is through legal support.

New to the offshore wind industry is a ‘one-stop shop’ that amalgamates expertise and contract management, and supports Alternative Dispute Resolution processes. Brookes Bell and ELAN Forensic have launched a commercial partnership that delivers expertise for every offshore wind-farm project and dispute.

It is important to choose legal support based on experience and skills in evidence gathering (for example non-destructive testing – to prepare the necessary evidence in litigation and arbitration cases is essential if claims are to be assessed and technically evaluated to the highest standards).

External experts can be appointed at any stage of the project, but early involvement provides the greatest returns. This ensures that consistent contracts with good case law are used from the outset. Internal teams can be trained in contract management approaches incorporating robust decision-making processes, correct allocation of responsibility, transparent and documented processes and the maintenance of records.

Amid changes in the legal landscape, it is essential that all those involved in the offshore wind supply chain are fully apprised of their legal position, and proactively manage their contracts and project execution to minimize the risks of disputes and to prepare in advance should commercial litigation arise.

Filed Under: Construction