Designing the most efficient and effective wind turbine calls for modeling tools that provide accurate, reliable numerical predictions of wind-turbine rotor performance over a machine’s full range of operating conditions. Simulating real-world conditions using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) lets users understand flow phenomena and their effects on the system, better predict the system’s power output, and analyze the types of vibration, fatigue, and other wear-and-tear the wind turbine may experience for the conditions modeled.

Such complex analyses are necessary for complex machines. Wind turbines, for instance, typically include:

- A bladed rotor for converting wind energy into rotational shaft energy;

- A nacelle housing a drive train, which usually consists of a gearbox to increase the rotational shaft speed, a electrical generator that produces a medium voltage, and a transformer that later increases the voltage of the electric power to reach its distribution voltage

- A tower to support the rotor and drive train, and

- Electronic equipment such as controls, electrical cables, ground support and interconnection equipment.

CFD simulation provides valuable insight into all aspects of wind-turbine development, from optimizing advanced blade designs to simulating and comparing the behavior of competing wind-turbine configurations. Engineers can evaluate various tip devices, such as spoilers, deployable gurney flaps, and other control devices to assess the impact of different hub and tower heights, and test and explore alternative scenarios and “what if” questions related to optimizing wind turbine designs.

This is especially important because many innovative designs being considered cannot be reliably modeled using conventional tools. For example, the classical Blade Element Momentum (BEM) method has been the prevailing approach for modeling wind turbines. While it is sufficient for modeling many applications, it is not able to adequately account for the impact of large 3D effects on flow, nor the impact of new blade geometries. Recent experimental work shows that CFD modeling can effectively simulate the behavior of novel blade geometries, with better results than from the BEM approach.

|

Reading the CFD Output

|

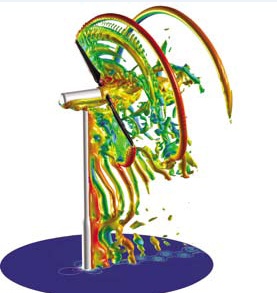

In the typical CFD workflow, the post-processing phase brings the simulation data to life. By breaking large data into smaller, more specific and manageable pieces, post-processing tools such as FieldView lets researchers easily and efficiently interrogate simulation results, identify the most relevant features of a design, and in so doing, create an iterative design optimization process in which the results of one simulation are incorporated into subsequent simulations. This process can be automated using tools such as FieldView FVX.

Post-processing also produces 3D color graphics, plots, and animations that display the simulation results in a meaningful and easy-to-understand format for presentation to various stakeholder groups, many of whom are usually not experts in engineering or the wind-energy domain.

In addition to providing a more rigorous and reliable modeling, CFD-based simulation can result in significant time and cost savings by reducing the need for scale models, wind-tunnel tests, and field testing. Small-scale test data can be effectively investigated and extrapolated to reliably predict system behavior at a larger scale.

Site selection, microsite considerations

Site selection is of paramount importance in wind-energy projects. Its goal is to identify locations with the strongest, most sustained overall wind patterns while avoiding wind shadows and highly turbulent areas. An emerging discipline called micrositing evaluates localized wind patterns and terrain effects, and helps engineers place the wind turbines in the most advantageous location within the selected site.

When evaluating competing sites for wind-based power generation, three factors are particularly important:

- High average wind velocities

- Optimal time distribution of high winds. For instance, does the wind tend to blow more in the afternoon when the grid needs the energy, or does it tend to blow after midnight, when demand for electric power is lower?

- Low turbulence levels.

Site selection is directly influenced not just by prevailing wind patterns such as speed, direction, and regularity, but by factors such as turbulence and altitude, which impact air density. Changes in air density come from temperature differences that occur because of heating by the sun, cooling from rain, or variations in the terrain, such as rocky areas adjacent to areas covered by vegetation. Nocturnal jets – streams of high-speed, turbulent flow that descend from the upper atmosphere in some clear-sky conditions – must also be considered because they generates large structural loads on a turbine.

The amount of energy that wind contains is a function of the cube of its speed. That is, when the wind speed doubles, the amount of energy it contains increases by a factor of eight. As a result, potential geographic locations are given a wind rating based, in part, on the average prevailing wind speeds at the site. In general, locations with a designation of Class 4, 5, 6, or 7 are considered commercially viable sites. Unfortunately, they are not that common.

Far more prevalent are the Class 3 sites, which are characterized by lower average wind speeds. To operate wind turbines at Class 3 sites, the engineering community is actively working to develop and commercialize various passive and active engineering advances in blade design and materials to maximize energy yield, reduce the cost per kilowatt-hour, and minimize wear-and-tear on the wind turbine blades, drivetrain, and other components.

Improving site-assessment techniques has become another goal. The complexity of the airflow at any potential location requires thorough quantitative and qualitative analysis, and the size of the data places special demands on the engineer and tools used to interpret and manage the data. Using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to model and simulate the environmental conditions associated with a given terrain lets engineers identify, characterize, and predict wind patterns, atmospheric turbulence, nocturnal jets, and other relevant factors quickly and effectively. Micrositing is also significantly enhanced by CFD modeling.

A typical CFD workflow begins with mesh generation and model development, and after specifying some of the prevailing flow conditions, such as wind speed and direction, a CFD solver runs to simulate and predict the density, velocity, and pressure of the airflow. The resulting large, unsteady datasets are then post-processed. Post-processing software such as FieldView from Intelligent Light, Rutherford, N.J. breaks the simulation data into smaller, specific, and more manageable bits, helping investigators more effectively interrogate the data to identify key flow features, characteristics, and visualize critical aspects of complex simulations. This improves overall data management and processing requirements, reduces the computational power needed, and increases the user’s speed and agility in analyzing and visualizing CFD results. Repetitive tasks can be automated with tools such as FieldView FVX, again speeding analysis and capturing a company’s knowledge and preferred calculations.

|

Wind Classifications at 10 M

|

Finally, post-processing produces high-resolution, 3D color graphics, plots, and animations that illuminate site aspects such as velocity vectors, pressure contours, and regions of constant flow-field properties. An ability to analyze and display the modeled results in a meaningful and easy-to-understand format is particularly important because these complex problems and modeled solutions must be shared with other stakeholder groups who are usually not experts in engineering or the wind-energy domain.

Today, CFD is being applied to a wide variety of issues in wind engineering. One major European wind turbine manufacturer, for instance, has successfully used STAR-CCM+ [CD-Adapco] and FieldView to develop design and siting tools. At the Sustainable Energy Solutions Group at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, researchers are working with the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority to study a wind site located in western Arizona. The location, Aubrey Cliffs, is a typical wind site in the southwestern U.S. It has numerous high elevations and ridge lines along the sides of mesa tops. These sites are thermally driven, with temperatures in nearby valleys (such as Phoenix) reaching more than 110F (43C). Researchers have been collecting wind data and predicting wind patterns in the area using flow solver codes such as Overflow from NASA and AcuSolve from Acusim Software, Mountain View, Calif. Post-processing with FieldView brings data sets from the solvers together and allows meaningful exploration of measured and simulated data.

Discuss ideas and comments at www.EngineeringExchange.com

::Windpower Engineering::

By Earl P. N. Duque, Ph.D. Manager Applied Research Intelligent Light and Associate Research Professor Northern Arizona UniversityFiled Under: Software

The CFD simulation of NREL’s unsteady aerodynamic

The CFD simulation of NREL’s unsteady aerodynamic