Wind developers come in all sizes. For those who would like to offset their electric bills with a small turbine or two, local ordinances provide sufficient guidance and permission. But those who would like to install units capable of generating a few megawatts and more will have to do a little homework. The homework in this case is a site assessment. It gets a bit involved and take some time but the payoff is worth the effort.

“We have this land…”

Many community members are land owners who have heard that leasing their land to windfarm companies could be profitable. “Big incentives for community wind are the financial benefits,” says Erin Edholm, Communications Director at National Wind in Minneapolis (nationalwind.com). “A turbine on your property can earn an annual lease payment, a typical feature of wind projects. The community or land owner may get a percentage stake in the wind company and revenue, an amount that depends on how profitable it is.“

Developments are divided into a few categories specifically, community-owned wind and traditional or corporate-owned developments. “Community wind can refer to small wind or utility-scale wind farms. National Wind has initiated a utility-scale community model where the threshold for development is 50 megawatts (MW), involving 20 to 30 commercial size turbines, covering several thousand acres,” says Edholm. Small community wind refers to a farmer and individual, for example, owning one or two turbines. Traditional or corporate owned wind projects are developer or utility-owned. The main difference between the two types is that with community ownership, the profits stay local while with corporate-owned wind farms, the revenue is retained by the developer or utility.

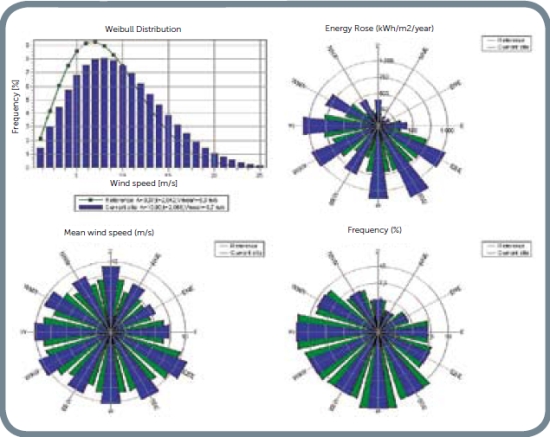

A first step in the development of a wind farm is to identify land with sufficient wind to support a commercial project. “This calls for a series of studies, one of which is the wind-study assessment that looks at historical wind data. There may be a meteorological or met tower in the area that has accumulated sufficient information. We might also look at weather archives and model-out on that data to find what a potential wind farm could produce,” says Edholm.

A wind assessment along with transmission and environmental studies, can also tell if it is feasible to put together several land owners to commercially produce power. Landowners can try to put together a wind project on their own but it’s a complex process that often benefits greatly from the expertise of a community developer. “Several business structures exist to develop community wind. One model involves the developer and the landowners investing capital to form a community owned company called a limited liability corporation or LLC.”

Assessments are not required by law, but certainly before permitting a wind farm, authorities ask for a lot detail about the wind regime that an assessment provides. “Also, banks providing the financing will require not just one assessment, but more likely two or three,” says National Wind President Kevin Romuld. Different firms use different techniques. With such a big price tag on theses projects, its common sense to get several assessments. If all two or three are within reason, the banks feel better.”

The assessment comes in different phases. The first is more prospecting, so we answer the question: What is the potential of this area? What are the prospective wind speeds in the area, and we can get point studies and look at state resource maps for a feel of the wind in a certain local?

“Once a group decides to pursue the project, it forms the LLC or a community group, and we look at details for siting met towers and how many,” says Romuld. “The main task is to start a data-acquisition program so we can gather data for at least a year.”

While the meteorological tower is collecting data, for example, companies like National Wind are planning things such as pinpointing the best wind resources in an area, looking for residences, roads, and set backs needed for historical sites, and microwave beams paths.

Romuld says a site assessment ranges from $15,000 to $30,000 not including met towers. They might add another $15,000 each. Typically, the LLC owns the tower so they can be taken down and relocated, or sold.

The met tower

When no wind history is available for a particular plot, a met tower will have to be erected and collecting data for at least a year. “You can also collect data from nearby airports and weather archives,” says Edholm.

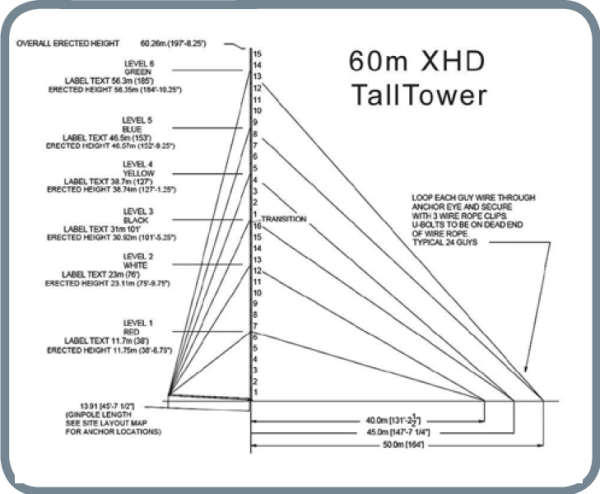

Met towers are available in 30 to 80-m heights. “Eighty meters is the hub height at which many current turbines work. Shorter designs require engineers to extrapolate data. They are, however, cheaper than the taller versions. The industry accepts data from both but in the interest of accuracy, the 80m tower may be preferred,” she says.

The 60-m XHD TallTower, from NRG Systems, Hinesburg, Vermont (nrgsystems.com) is ice-rated for extreme climates, and exceeds EIA- 222-F Standards. Its sturdy galvanized steel tube construction makes it reliable and easy to transport to remote sites. Tower tube sections slide together, then tilt up from the ground using a ginpole and winch. No cranes or concrete foundations are required for installation. NRG TallTowers are supported with aircraft cable guy wires and anchored with standard screw-in anchors (other anchor types are available for various soil conditions). The XHD tower includes a grounding kit.

When developing a sufficiently large property, it’s necessary to look at a couple different footprints or parcels. “Companies like to put projects together in phases. These could be for example, 100 MW portions of a 300 MW wind farm. A utility does not want to buy 300 MW at once typically because it is expensive for them as well. But 100 MW is a generally accepted threshold, for utilities although it can vary dependent upon their needs. Utilities often require on-site met tower data for each footprint,” says Edholm.

Engineers would first look at each footprint and select a spot representative of the parcel for the tower. Putting up a tower requires a signed lease from the land owner.

For its year of operation, the tower collects wind direction and speed, atmospheric data, seasonal changes, and patterns of wind speed. “That information is fed into modeling software that provides other information for planning the wind farm,” she says.

Software used in the assessment also helps establish a setback from homes for the wind farm. “This is to make sure residents endure only minimal noise and shadow flicker. This latter event occurs on sunny days when the rotor’s shadow passes over a building. Flashing or flickering bothers some people. Simulation software now predicts the effect and helps us avoid it. Software also calculates the cumulative flickering during the year. There is no universal standard for the number of hours a person might tolerate, but a German standard has set a period of not more then 30 hours per year as a maximum exposure,” says Edholm. “This is a commonly accepted standard and all assessment groups try to mitigate shadow flicker exposure as much as possible.”

The environmental assessment

A lot of wind-farm work is in agriculture fields. “These parcels have good visibility, so generally we walk across the project area with plans in hand considering what will be altered by the construction,” says Dean Sather, principle investigating archeologist with Westwood Professional Services Inc, in Eden Prairie, Minn., (westwoodps.com). Plans from the client tell where the roads will be, where the cables will be laid, and where the turbines will be sited. “Archeologists often say ‘let the dirt do the work’, meaning, we research the nature of the soils in an area and let the geologic history tell us what’s happened there and how it might have impacted the area’s archaeological history. In other words, let the soils be an interpretive feature of the landscape.

So we walk through the area looking for artifact densities and evidence of prehistoric occupation. In plowed fields away from water, most of the telltale artifacts will be on the surface,” says Sather.

His team occasionally finds stone tools or broken pottery. “We look for the indicators of prehistoric occupation on the landscape. The nearness to water is one indicator. Then we look for evidence that it might be a farmstead from the early days of the frontier.

Good news for wind-farm developers is that there is little in the terms of discoveries that would halt a wind farm. “Many of the archeological sites we find are relatively small and most developers understand that they may have to shift a turbine 100 meters, or route a cable around an archeological site. So that does not halt a project. As you’d expect, the earlier we get into the field the better we can provide planning information.”

Identifying habitat is another preliminary study. Sather say his firm does a critical issues analysis by collecting information on wetlands and finding the CRP (Conservation Reserve Program) land. This is land set aside that farmers leave in grassland or untilled. “We collect as much as possible, getting information on protected or endangered species, and finding their habitat range,” he says.

Another task for companies like Sather’s is to evaluate the visual impact of the development. “Of course, we would not recommend placing turbines atop Mr. Rushmore. But one question can be: What visual effect will turbines have on the landscape? This is critical when the farm will be close to tribal land or sacred sites. We find those sites and use software to show how the turbines would appear from the local, and consider how we might minimize the visual impact.”

An archeological crew from Westwood Professional Services, Eden Prairie, Minn, takes a closer look at a potential turbine site.

Getting wind power on the grid

Large facilities draw a lot of power from a grid so grid owners want to know how much and when they will need the power. A similar question is asked on the opposite side of the coin when a wind farm wants to inject power into the grid. Its owners want to know: How much and when? “Of all things one encounters in this world of power generation, regardless of source, this permission to inject power is hardest to get, at least in the Midwest,” says Jack Levi, co-founder of National Wind and grid assessment manager. “If you want to inject 100 MW you might have to wait three to seven years. And it’s getting worse. Imagine the highway traffic in your area. Now imagine twice as many vehicles on the same roads. There may not be room for them. The same is true of the grid because of the lack of good transmission capacity. Like roads, it takes a long time to build more grid.”

Levi says the process works like this: First, a wind farm applies for an interconnection. “A feasibility study begins. To permit an amount of power, grid owners study the effect of injecting so much power into the lines by considering what it would do to all the substations and other lines in the grid. It is a daunting task. If the power injection were done haphazardly, it could trigger faults like the ones that blacked out the East coast several years ago. So the study starts by asking is the 100 MW allowable? Then an impact study looks at what is being affected. This could take two to three years,” he says.

Once the grid operators have a list of all lines affected, the impact study proposes mitigations and fixes. Engineers conducting the study make recommendations that might say “upgrade these lines”. Then a facility study examines the cost of the upgrades and how long they will take.

A final step signs a connection agreement to make the fixes and pay for them.

“Presently, half is paid by the generator and half by the transmission owner. But there are proposals to make it all payable by the generator,” says Levi.

As you’d expect, there is a Federal agency overseeing activities that relate to the electric grid. “The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission or FERC is a little like a judge who also makes rules. If a complaint is made, you go to the FERC and say, ‘This is illegal because it goes against this tariff.’ The organization would decide whether or not that is the case. It also legislates or issues rules, and makes judgments as to how well people abide by the rules,” he says.

The FERC recently released its strategic plan for 2009 to 2013. It’s available at ferc.gov.

Filed Under: Community wind, Construction, Featured, Policy