One of the 11 Siemens turbine nacelles arrives on site. Using the sale-leaseback financing approach, the turbines were sold to a Union Bank affiliate and proceeds helped pay off the construction loan and initial rent.

Woodstock Minnesota may bear the same name as its New York counterpart, but instead of a stage full of musicians, it sports a field full of wind turbines. The 11 Siemens SWT 2.3-MW units of the Ridgewind farm are a source of power for 10,000 homes and local businesses. But more importantly, they are a testament to the first successful sale-leaseback financing of a wind project, and to the investments and hard work of the surrounding community.

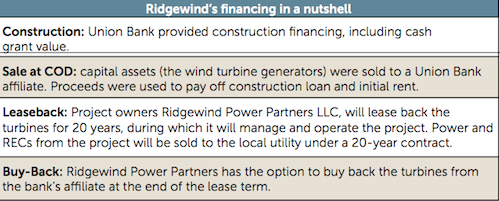

Minnesota- based project resources Corporation (PRC) developed and constructed the 25.3-MW project with $51 million in construction financing from Union Bank in California. Now, with the project operating commercially (as of last December), this construction loan has been paid off as part of a 20-year, sale-leaseback financing with a leasing affiliate of Union Bank. In sale-leaseback, the project sells the turbines to the leasing company, which then leases them back to the project for 20 years. This allows financing the project with a single investor─in this case Union Bank ─or, as PRC President Paul White puts it, makes financing a “one-stop-shop.”

White says using a leaseback structure made the project financing simpler, with potentially better annual payment terms than a partnership deal with debt and a tax investor. For example, leaseback involves financing with a single investor, so you’re dealing with just a single entity for both construction and permanent financing. As Berkeley’s National Laboratory’s Community Wind: Once Again Pushing the Envelope of Project Finance report explains, this simplifies the financing process and eliminates the possibility of troublesome creditor issues that can often arise between tax-equity investors and lenders. White says this method works well for small projects such as Ridgewind. “It helps not to have to deal with multiple banks or investors,” he says. “It means fewer lawyers and lower transaction costs.” Another advantage of leaseback financing is longer tenor. The financing term may extend 20 years versus only 15 in straight financing, and depreciation benefits are rolled into the lease rate. “The lease financing simplifies project accounting as the payments are simply a project expense,” White says.

The Ridgewind project also applied for a U.S. Treasury Cash grant issued under the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act. This drives down the equity required and leaves Union Bank with tax benefits. According to Berkeley’s report, this means that project investors need not have any tax appetite at all, whereas in a partnership-financing structure some portion of tax benefits will be allocated to the project owners, whether or not they can use them. Lease financing could potentially broaden the base of tax investors interested in wind projects, according to the report. Typically, many large institutional tax equity investors won’t bother with smaller community-wind projects, but many smaller banks have affiliated leasing companies that might have more interest.

All these advantages make a “single- investor” sale-leaseback structure a good option for community wind projects, according to White, especially for smaller projects that can’t afford a large budget for transaction costs. However, this approach may not be appropriate for bigger projects. “A project of, say, 100 or 200-MW can cost $200 to $500 million to build,” White explains. “Such larger projects will undoubtedly involve multiple investors pulling together for the total financing, including a lead bank, a tax-equity investor, and follow-on banks or investors. In such a scenario, each bank or investor will have its own legal council, which will significantly push up transaction costs. Financing becomes more complex when there is more than one financial institution involved in the deal.”

Another interesting aspect of the Ridgewind project was that local farmers were able to invest. After the project began commercial operation and the sale-leaseback financing closed, PRC expanded community ownership through its Minnesota Windshare program, opening a portion of Ridgewind Power Partners, LLC to local investment. White explains the program was inspired ten years ago when PRC saw that farmers want to invest in wind, but didn’t have much time or appetite for the risky project development and construction process.

“Wind energy makes sense to farmers,” he says. “They trust the wind and want to make use of it, like farming another crop. But wind development is technical, challenging, and risky.”

PRC President Paul White (right) stands next to a foundation bolt cage for one of Ridgewind’s turbines. Project construction commenced in late 2009 and completed in december 2010. The wind farm is expected to produce about 85,000 MWh annually.

At the same time, PRC wanted to avoid raising eyebrows of bankers that are often uncomfortable with local partners. “Banks and tax investors rely on professionals that know the business,” White says. “They don’t have patience for uncertainty.” So the company created a model where they develop and construct the project and invite the community to invest alongside PRC afterwards. “Not only does this keep the bank happy, but this way local investors can take a hard look at the finished product,” White says. “They can kick the tires and decide if they want to invest or not with more certainty.” Working in cooperation with local utility Xcel energy and Union Bank, PRC retains management control of the facility from day one.

Other community wind developers can certainly benefit from this type of financing, and White offers them some advice. He says it’s helpful to have a financial adviser, as PRC had Miracol energy LLC of new York to advise in Ridgewind. Also, he stresses the advantages of inviting the community to invest only after achieving commercial operation. “This can simplify the process a lot,” he says. “I think it helps the local community get a handle on a project before they make decisions about whether or not they want to participate.”

WPE

Filed Under: Community wind, Construction, Financing, News, Policy, Projects