New York recently announced the largest procurement of offshore wind power in U.S. history: to develop 9.0 GW of projects by 2035. New Jersey has set a goal of 3.5 GW by 2030. Barely a year after Massachusetts pledged to at least 1.6 GW of offshore wind, the Department of Energy Resources released a report recommending the Commonwealth doubled that commitment. Connecticut has signed on for 2.0 GW of offshore wind. There are others.

Several U.S. East Coast states have set ambitious targets to build offshore wind projects. For the sector to succeed in the U.S., developers will require a reliable workforce and supply chain — including ports, vessels, and component suppliers — to keep up with demands

Over the next two decades, East Coast states and California expect to develop more than two-dozen offshore wind farms. The interest in an American offshore industry is clear. Next, however, comes the how. Building a supply chain — and, specifically, port infrastructure that supports the unique requirements of offshore wind — is critical to industry advancement.

“Timing is everything and congestion could be a major problem over the next decade,” says Lars Andersen, president of K2 Management’s North American operations. K2 is an experienced owner’s engineer and lender’s technical advisor. “For example, a single port harbor facility will be overburdened if multiple projects are under construction at the same time. Therefore, developers will likely have to consider multiple facility strategies and secure their options well ahead of time.”

Andersen expects (and recommends) a cooperative approach to emerge between wind developers and port owners and operators. His sentiment is shared by a recent report released by the Business Network of Offshore Wind, a non-profit dedicated to establishing an offshore wind supply chain in the U.S.

The report states that both U.S. coasts must cooperate on several important fronts —including for transmission grid development and supply chain support — to sustain a successful offshore wind industry for the country.

“States, such as Massachusetts New York, and others, are working to build an industry to protect the environment, generate jobs, and provide affordable renewable energy,” says Liz Burdock, president and CEO of the Network. “They are competing with other U.S. states…and rightly so. But states must also cooperate to minimize public costs, share resources, and globalize what the U.S. has to offer.”

Andersen agrees. “As different ports will provide different capabilities, expect to see more public-private partnerships, ad-hoc agreements, and regional pacts moving forward,” he says. “Ultimately, a reliable offshore wind sector in the U.S. will depend on high-quality port infrastructure, and lots of it.”

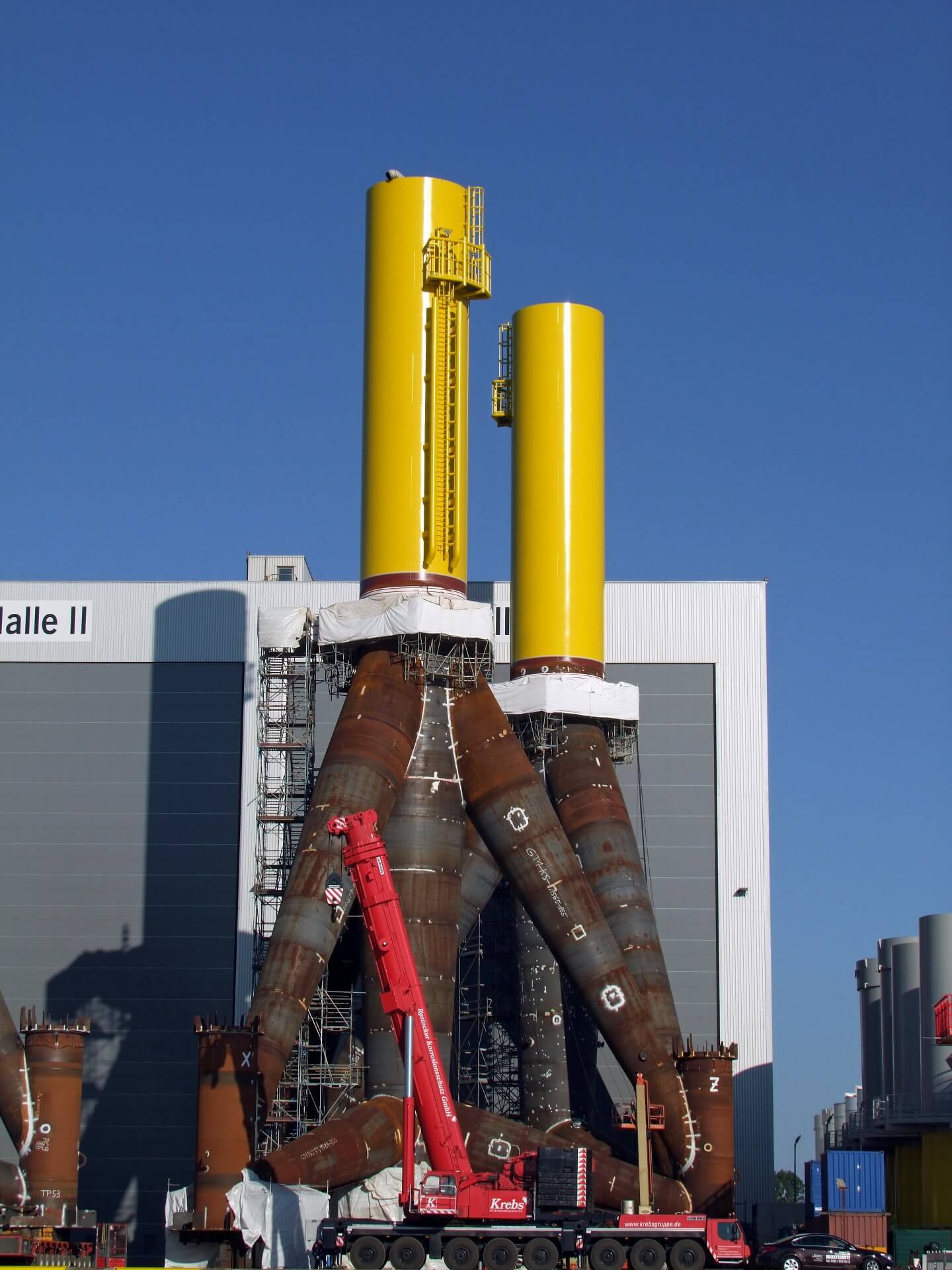

Such quality infrastructure must include heavy-lift capacity, adequate laydown for the handling and storage of large components, unimpeded access in and out of the harbor, geographic proximity to the project site, and zero air draft restrictions for wind-turbine construction efforts. “Currently, however, there are no East Coast ports that hit every note for the current slate of projects proposed,” Andersen points out.

A hurricane gate at the mouth of New Bedford harbor in Massachusetts limits vertical vessel clearance to 150 ft. Last year, the U.S. Department of Transportation awarded a $15.4 million grant to the Port of New Bedford to support its offshore wind staging efforts. (Credit: Mary C. Serreze)

He provides a couple of examples in Massachusetts:

- New Bedford Marine Commerce Terminal received $15.4 million in federal funding to improve the infrastructure and environment of the port, primarily to support offshore wind and the fishing industry. This is great news because New Bedford is capable of handling heavy loads — but the shipping channel is protected by a hurricane barrier with a 150-foot horizontal opening.

- Brayton Point, a former coal plant in Somerset, is currently re-developing into an offshore wind hub with advanced grid services, heavy-lift capacity, and a substantial area to hold and stage components. However, the ability of specialized jack-up vessels currently required for offshore construction is limited due to the nearby Mt. Hope Bridge’s 135-foot, under-height clearance or air draft restriction.

New Jersey’s Port of Paulsboro presents a similar challenge because of its proximity to a bridge and power lines that prevent offshore developers from using safely or efficiently as a hub to transport turbines to sea.

“Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia are all promoting their state’s port infrastructure sure it’s on the radar,” says Andersen. “You can search up and down the East Coast for the ideal offshore wind staging port, finding pros and cons with each one. But there is not one home run.”

This makes sense. American ports were never designed for offshore wind. Offshore developers may have to sacrifice an ideal setup for the next best case.

In Europe, for example, large installation vessels will enter a port, transport components to the wind site, and stay onsite until after installation. In the U.S., access constraints in and out of a harbor will likely impede this approach.

Nevertheless, U.S. marshaling ports are already being “claimed.” Offshore developer, Vineyard Wind, has signed a $9 million, 18-month lease at the New Bedford terminal for its 800-MW project. Ørsted and Eversource, which won several BOEM (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management) offshore auctions, signed a 10-year lease at the New London State Pier, and have partnered with the Connecticut Port Authority to develop a $93 million facility there. Other agreements are also in the works.

“Project developers are already committing significant resources to secure their preferred port sites,” says Andersen. “There are a lot of moving parts, with states competing for private sector investment and developers competing for ports and installation vessels. With the growing project pipeline, the market for port facilities will be very active throughout the next several years.” And likely for several years post wind-farm construction.

O&M considerations

Following a project’s commissioning and operation, operations and maintenance (O&M) teams will also require ports for transportation of personnel and components (for repairs or upgrades).

Thanks to insight and feedback from about 100 offshore wind experts in the U.S. and overseas, the Business Network for Offshore Wind’s Leadership 100 report recommends steps to ensure American success in the developing offshore industry. The steps touch on state policies, supply chain efforts, and electrical transmission requirements.

“Certainly, the development of ports and port infrastructure is imperative,” Burdock points out. “In addition, other critical issues for offshore success include ensuring enough transmission capacity and interconnection points to the electric grid, as well as reliable workforce development for wind-farm construction and O&M.”

An O&M port serves as the transition between an offshore wind farm and land-based activities. “Such a facility needs to be close enough to the offshore project to limit transit time from shore while also providing adequate support for supply chain infrastructure and the efficient movement of workers or wind technicians, and supplies,” says Andersen.

He suggests developers consider their long-term O&M and site access strategy prior to selecting their port of choice. Some questions to consider:

Will the offshore wind site be accessed using conventional crew-transfer vessels (CTV) or would it be better served by larger service and operations vessel (SOV) – or a combination of the two? SOVs can transport larger quantities of spare parts and tools that CTVs, and typically also serve as a temporary hotel, so the crew can stay overnight if necessary instead of going back and forth to land.

“Many potential East Cost O&M base sites in close proximity to the projects have the water depth to support CTV operations but not SOV operations,” he says.

How quickly can the port accommodate O&M crew schedules in the event of unexpected maintenance? And are there time or seasonal restrictions? On the East Coast, at least, wind projects would likely adhere to a seasonal window for construction and maintenance – typically April through October.

The Northeast coast of the U.S. is heavily developed, he points out. “Most shoreside harbors are popular resort areas that are surrounded by vacation homes and have significant levels of pleasure craft traffic. It can be challenging to permit new commercial uses in these areas and shore-side logistics in the summer months can also be challenging due to seasonal congestion.”

What is the port’s storage capabilities for spare turbine components? This is to ensure such parts are available on-demand to reduce turbine downtime.

Is there a “Plan B”?

Making plans based on proposed future improvements at a port facility is risky, says Andersen. “The sources of funding and the permitting timelines should be carefully evaluated. Developers are always contemplating a ‘Plan B,’ but second options can be tough to find when there are limited alternatives.”

“Regardless of the chosen path, siting of an O&M facility requires a long-term, flexible strategy and early engagement with local stakeholders,” says Andersen. This means communication and cooperation skills are critical for offshore success.

“Forming respectful partnerships early on will certainly be the key to establishing and maintaining a presence in these top East Coast harbors,” he says.

“As the U.S. offshore wind supply chain takes shape, the industry will revitalize the country’s ports and their surrounding areas, which means supporting businesses and the workforce in America,” adds Burdock. “The more we work together, the stronger the offshore wind industry can be.”

A renewable energy hub

As U.S. ports work to revitalize or reform their infrastructure along the East Coast to support the developing offshore wind sector, each may offer different benefits (or challenges) depending on location and local marine regulations.

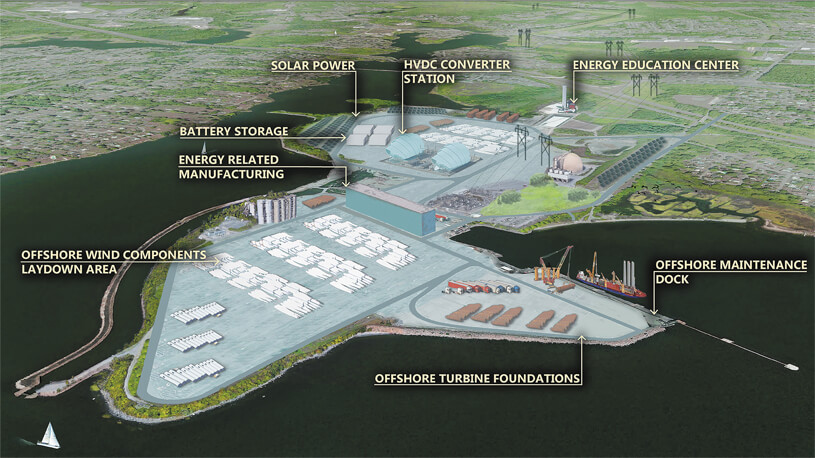

Brayton Point Power Station in Massachusetts will transform into Anbaric Renewable Energy Center.

The recently announced Anbaric Renewable Energy Center, which will transform Brayton Point Power Station in Massachusetts — a former coal-fired power plant — to a logistics port, manufacturing hub, and support center for the offshore wind industry, serves as one example.

“The Renewable Energy Center represents Anbaric’s broader vision for its Massachusetts OceanGrid project: high-capacity transmission infrastructure to maximize the potential of the region’s offshore wind energy resource,” said Edward Krapels, CEO of Anbaric, in a press statement. The company specializes in early-stage development of large-scale electric transmission systems and is working with Commercial Development Company’s Brayton Point LLC.

Although a nearby bridge may force height restrictions for wind-turbine towers to and from the port, the Renewable Energy Center marks a significant commitment and investment in the offshore wind industry. The Center will include a 1200-MW high-voltage, direct-current converter with 400 MW of onsite battery storage.

What’s more: the Brayton Point Commerce Center is equipped with a 34-ft deep water port capable of berthing large trans-Atlantic merchant vessels, which were formerly used to import coal. This means the port will also be used for bulk cargo, heavy-lift cargoes, and building materials for the offshore wind sector.

“Developing a landing point for 1200 MW of offshore wind at the site of a former coal plant physically and symbolically represents the transformation from fossil fuels to wind,” added Krapels.

Filed Under: Featured, Offshore wind, Projects