This is the executive summary from a report issue by NREL.

Historically, federal incentives for renewable energy development in the U.S. largely consisted of the investment and production tax credits (ITC and PTC), the accelerated depreciation benefit for renewable energy property [the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS), and the bonus depreciation]. The ITC and PTC provide financial incentives for development of renewable energy projects in the form of tax credits that can be used to offset taxes paid on company profits. Given that many renewable energy companies are relatively nascent and small, their tax liability is often less than the value of the tax credits received; therefore, some project developers are unable to immediately recoup the value of these tax credits directly. Typically, these developers have relied on third-party tax equity investors to monetize the value of the main federal incentives for renewable energy project development.

However, in the wake of the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the pool of tax equity investors significantly decreased, limiting the ability of renewable energy project developers to recoup the value of these tax credits. To minimize stagnation in the renewable energy industry as a result of the weakened tax equity market, the Congress created the §1603 Treasury grant program under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (the stimulus program). This program offers renewable energy project developers a one-time cash payment—in lieu of the ITC and PTC and equal in value to the ITC (30% of total eligible costs of a project for most types of energy property)—thereby reducing the need for project developers to secure tax equity partners.

Although the primary intent of the §1603 program was to minimize the impact of the weakened tax-equity market on renewable project development, as part of the Recovery Act, the program also had “the near term goal of creating and retaining jobs” in the renewable energy sector.

In some cases, says NREL, totals may not equal the sum of components do to independent rounding and preservation of significant figures.

This analysis responds to a request from the Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (DOE-EERE) to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) to estimate the direct and indirect jobs and economic impacts of projects supported by the §1603 Treasury grant program. The analysis employs the Jobs and Economic Development Impacts (JEDI) models to estimate the gross jobs, earnings, and economic output supported by the construction and operation of solar photovoltaic (PV) and large wind (greater than 1 MW) projects funded by the §1603 grant program. As a gross analysis, this analysis does not include impacts from displaced energy or associated jobs, earnings

Through November 10, 2011, the §1603 grant program has provided about $9.0 billion in funds to over 23,000 photovoltaic (PV) and large wind projects, comprising 13.5 GW of electric generating capacity. This represents roughly 50% of total non-hydropower renewable capacity additions in 2009 to 2011.

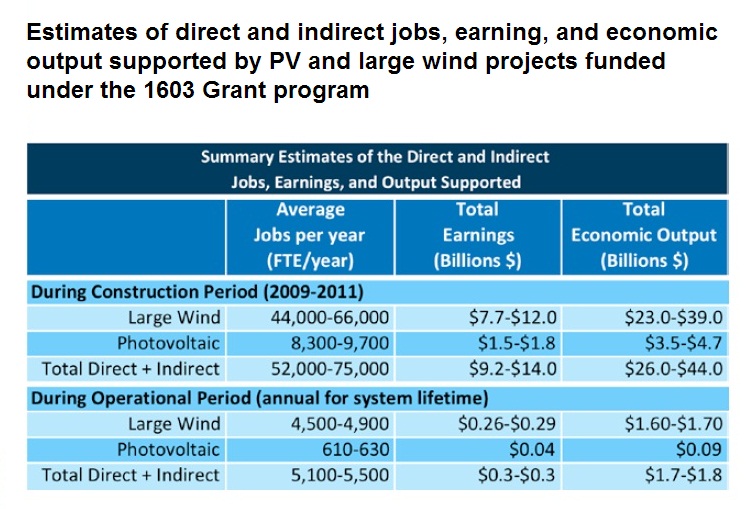

The estimated gross jobs, earnings, and economic output supported by the PV and large wind projects that received §1603 funds are summarized below and in

Table ES-1:

• Construction- and installation-related expenditures are estimated to have supported an average of 52,000 to 75,000 direct and indirect jobs per year over the program’s operational period (2009 to 2011). This represents a total of 150,000 to 220,000 job-years. These expenditures are also estimated to have supported $9 billion to $14 billion in total earnings and $26 billion to $44 billion in economic output over this period. This represents an average of $3.2 billion to $4.9 billion per year in total earnings and $9 billion to $15 billion per year in output.

• Indirect jobs, or jobs in the manufacturing and associated supply-chain sectors, account for a significantly larger share of the estimated jobs (43,000 to 66,000 jobs/year) than those directly supporting the design, development, and construction/installation of systems (9,400/year).

• The annual operation and maintenance (O&M) of these PV and wind systems are estimated to support between 5,100 and 5,500 direct and indirect jobs per year on an ongoing basis over the 20 to 30-year estimated life of the systems.

Similar to the construction phase, the number of jobs directly supporting the O&M of the systems is significantly less than the number of jobs supporting manufacturing and associated supply chains (910 and 4,200 to 4,600 jobs per year, respectively).

The estimated ranges reported reflect uncertainty in the domestic content of a system and its components—the portion of total project expenditures spent on U.S.-manufactured equipment and materials such as turbines, towers, modules, or inverters. Based on a review of a number of studies specifically addressing domestic content for these types of systems, and recognizing the complexity and changing nature of solar and wind supply chains, a range for domestic content was applied in the analysis. This included a low of 30% to a high of 70% for both solar and wind systems, spanning the ranges observed in the literature. The lower end of the impact estimates noted above reflects the 30% domestic content assumption while the higher end reflects the 70% assumption. While this range reflects the implications of uncertainty in one key input to the economic impact estimates, it should not be construed as fully bounding uncertainty in the ultimate estimates of the economic impacts. Total investment in these projects, which includes capital investments from all private, regional, state, and federal sources (including §1603 funds), is estimated to exceed $30 billion. These PV and large wind projects account for about 94% of the total generation capacity of projects funded under the §1603 program and represent 92% of total payments.

The results presented in this report cannot be attributed to the §1603 grant program alone. Some projects supported by a §1603 award may have progressed without the award, while others may have progressed only as a direct result of the program; therefore, the jobs and economic impact estimates can only be attributed to the total investment in the projects.

In addition, this effort represents a preliminary analysis of the gross impacts of the PV and large wind projects supported under the §1603 grant program rather than precise forecasts of the national economic and job-related impacts from these projects. Understanding the net employment and economic impacts of these projects would require a more detailed analysis of the types of jobs supported as a result of changes in the use of existing power plants and associated fuels, electric utility revenues, and household and business energy expenditures. Similarly, estimating jobs associated with possible alternative spending of federal funds used to support §1603 projects would require additional analysis.

Lastly, this analysis solely focuses on the jobs, earnings, and economic output supported by projects funded by the §1603 program. For a discussion of the impacts of the §1603 program on installed renewable generation capacity, project financing, and tax-equity markets, see Brown and Sherlock and Bolinger et al. The full report is here: http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy12osti/52739.pdf

NREL

NREL.gov

Filed Under: Financing, News, Policy