Here’s the state of the wind industry in two paragraphs: Construction is shifting from the Midwest to states with Renewable Electricity Standards. There is a big push is to get costs out. OEMs prefer lean manufacturing principles to slice costs from components. Turbine OEMs have cut costs by about 25% over the past decade and must trim another 15% to be competitive with natural gas – now the least expensive way to produce electricity. A national RES would be a boost to the industry. Without one, expect the industry to struggle.

The wind industry can also learn from the tragedy in Japan. Auto production is slowing due to Japanese parts shortages. The earthquake has shaken faith in lengthy and reliable supply chains, bringing the advantage of short supply chains into crystal clarity. Hence, OEMs are looking for closer services. The logistics of supply chains involves transportation, specialty tasks with challenges all their own, and topics that will be dealt with later. For more insight and to better understand the market, one consultant suggests looking for the challenges of your customer’s customer.

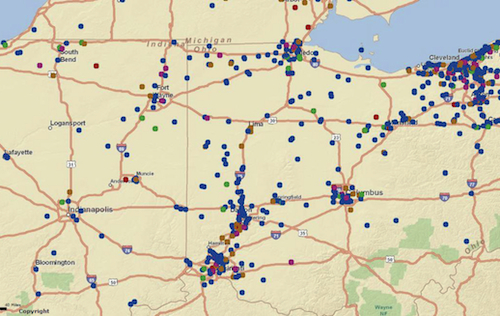

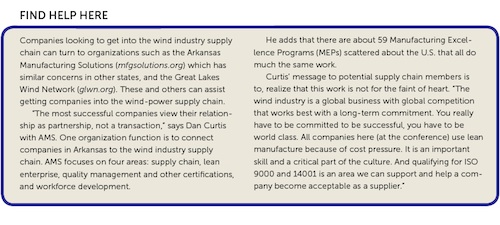

GLWN says it is dedicated to building a supply chain throughout North America through a network of 1,600 manufacturers, and with a mission to increase the domestic content of North America turbines. CEO Ed Weston says the organization works as a supply chain head hunter for OEMs, manufacturers, contractors, O&M firms.

The OEM’s perspective

OEMs want more than parts from their supply chain. They want to design cost out of products, not squeeze it out with cheaper materials. Also expect minimum lead times, no fixed volumes, rigorous supplier quality standards, and warranty and spare-parts support for 20 years. Another OEM suggests a goal of generating power at a lower cost than coal by 2020, and without subsidies. Here’s more thinking from several OEMs and owner operators.

At a recent conference, the supply-chain manager of Mitsubishi Power Systems America, Matt Carr, said his company will open an online Supplier Portal to provide qualification forms so applying vendors can upload their information. Carr said the portal allows better synergy across all MPSA plants and fosters supplier success.

What bothers Carr is the absence of a national RES and, as he says, the “hollowing out” of U.S. manufacturing. That is, there is no one-stop shopping so a large casting, such as a hub, has to be trucked to a separate machining facility–a trip that adds time and cost. Transportation, as others note, is at the top of their waste list because it adds no value and exposes the part to damage.

Mitsubishi which plans on launching a 2.4-MW turbine next year, is looking for about 50% domestic content, large and small castings, and more. Expect to sign a nondisclosure agreement when conversations begin with OEMs.

The manager of purchasing and logistics for Acciona, Tom Waggoner, presented another view of supply-chain concerns. “The Acciona 1.5-MW turbine has 78% U.S. content, which means the company is committed to North America.”

He admitted that current business fundamentals are not good, and forecasts are not much better. “For instance, with the downturn in the industry, there are 13 GW of wind-turbine supply chasing 5 to 6 GW of demand, and large trade agreements don’t exist anymore,” he said. “To add to the market confusion, rapidly changing technology and increased competitiveness for just about everyone is a sign of the time.”

Suppliers, says Waggoner, are expected to assist with OEM dilemmas. For example, OEMs are facing delayed payment terms. “Some customers want to make later payments and others want us to finance COD,” he said. “Longer warranties are also being considered, which may require longer coverage periods from suppliers. Extended warranties and its related topic of warranty recovery is a recent development. Things will wear out as machines age. Although, that is an opportunity for O&M teams.”

Waggoner also suggested several elements critical to a successful supplier-OEM relationship. For example, bench-marking and shrinking lead times will challenge all. Wind-turbine lead times have gone from two years, to six to nine months. “Adding people and machines won’t shrink the lead time because it does not fit the business model. It just adds cost.”

Waggoner also stressed the global-local presence, meaning the company wants a local presence with a global feel. “Vendors will have to provide full-service support on a global basis no matter where the wind farm,” he says. “We have to arrange a supply chain to deliver those expectations. So to be successful, we have to foster key supplier partners to build an effective collaboration model.”

The company’s qualification process is structured to increase supplier involvement for greater collaboration in design, and to implement best practices. One plan is to structure supply agreements with options contingent on success. The most competitive pricing will come by understanding the cost drivers and eliminating waste through lean manufacturing.

Waggoner tells of a recent supplier conference in which participating suppliers stressed their preference for early involvement in a project. “I was glad to hear that because it said ‘everybody gets it’. It means they understand the value that can be gained from design-for-manufacturing ideas. The earlier the involvement in the process, the better you can design a product for manufacturing. It also brings about standardization. So the earlier in the process, the greater the return.”

Waggoner tells of a recent supplier conference in which participating suppliers stressed their preference for early involvement in a project. “I was glad to hear that because it said ‘everybody gets it’. It means they understand the value that can be gained from design-for-manufacturing ideas. The earlier the involvement in the process, the better you can design a product for manufacturing. It also brings about standardization. So the earlier in the process, the greater the return.”

He also acknowledged the value of collaboration when asking: How can we win together? “Every OEM has fundamentally the same process with some differences,” he said.

Winning together can be done with standardized products and standard work procedures. Contracts will focus on terms of supply information, not volume. Suppliers must eliminate waste and nonvalue-add cost drivers, and leverage best practices and benchmarking. Change is uncertain but success is determined by those willing to do what others are not.

In a nutshell, said Waggoner, a successful relationship is built on the basis of cost, quality, delivery, and technology, with technology being key. OEMs also want to know what type of investment a supplier is willing to make and how they turn their ideas into rapid prototypes. Adapting to change will be key. He said it’s not about an ERP system, but improving and sustaining a current business level and then growing the business.

An operator’s perspective

An operator’s perspective

Invenergy’s Procurement and Supply Chain Manager Utopia Hill offered an operator’s perspective of the supply chain. Invenergy and its affiliated companies have over 6,600 MW of wind, solar, and thermal projects under contract, in construction, or in operation.

At the end of 2010 in the U.S. wind industry, she said, there were more turbines out of warranty than in warranty. The average turbine has a 20 to 25-year certified life, while most OEMs offer two to five-year warranties. “That’s a bit shocking because my car has a longer warranty than most wind turbines,” she said.

Also, there is no ‘Turbine Zone’ to go to for parts, she said, referring to the readily available AutoZone car-part stores. When comparing installed capacity in the U.S. market for the last two to five years, 6,000 to 16,000 turbines nationwide potentially could be out of warranty.

After-market support focuses on wind plants or turbines. “On the plant side, we look for support of substations and electrical components, collector systems and transformers, roads and transport, and safety and security, among others. On the turbine side, needs fill an extensive list that starts with gearboxes, yaw drives, bearings, and alignment services,” she said. “Owners and operator concerns boil down to: availability, availability, and availability because a turbine out of service equals lost revenue.”

Scheduled maintenance at her company starts with a weather forecast. “We prefer planned outages for a turbine rather than unplanned,” she said. “The company has compiled wind stats for years, so if we know the weather patterns, we can take a turbine out of service on a day in June or July when there is a lull between noon and six. We’ll schedule maintenance then. But in December when the wind is strongest, the turbine should stay in service.”

Hill says a way to extend service periods is to use condition monitoring equipment. “If the it indicates a potential failure, O&M teams can plan a repair or maintenance activity in a controlled way and on our terms. This avoids a catastrophic failure.

Just consider the huge financial impact from an unanticipated gearbox failure. Aside from the cost of replacing the gearbox, which is $100,000, getting the crane on-site plus labor and time kicks the figure to $200,000 alone. Consider the lost revenue for 30 days along with other costs and the total expense ranges from $315,000 to $600,000.

To fix such problems, Hill says the company is looking for people with solid working experience in the wind industry or a similar one. As an operator, the company has to maintain everything from the turbine to the point of interconnection. “Owner-operators like Invenergy are looking for quality parts and services at competitive prices.”

As more turbines come out of warranty there will be huge demand for support services, spare parts, and maintenance. Hill suggestes that interested companies start at www.ebidexchange.com/invenergy.

WPE

Filed Under: Featured, News