By Steven Bushong, Associate Editor

Wind turbines are learning to talk. Just as a patient shares symptoms with a doctor, wind turbines are increasingly able to communicate to each other and their manufacturers, decreasing the number of unexpected faults while increasing energy production.

The language is data or, depending on the scale of information, big data. This is a blanket term for an information mass so large that the most dedicated analyst would shutter the thought of organizing it. But with appropriate computing power, big data can produce impressive results, such as fraud protection on credit cards. It can also work in the windpower industry.

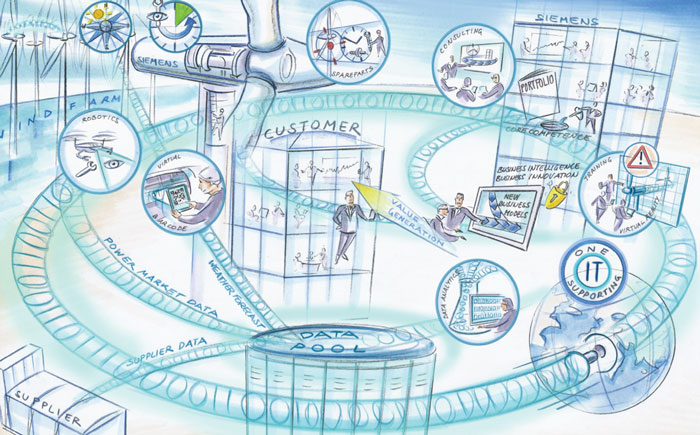

Siemens has illustrated their vision that big data would have in the windpower industry. Data would involve most business segments, routing information from suppliers and turbines in the field to a central collector, where it’s analyzed and made helpful to trainees, technicians, and business decision makers.

Already, utilities and owner-operators use big data to forecast power production and develop the best layouts for wind plants. In the future, however, companies could leverage data on a more micro level, turbine-by-turbine. One day, maintenance crews could be called to a tower just before a part breaks.

To pull actionable information from data, computers need a huge quantity of it – the more data, the better. For instance, Siemens has plans to analyze data streams from thousands of turbines, but it’s really a model the whole industry could follow and participate in, says Shuangwen Sheng, a Senior Engineer at the National Wind Technology Center at NREL.

“If all sectors shared information on turbine operational history – OEMs, owner-operators, before and after warranty – we could learn a lot more. The challenge right now is they don’t communicate,” Sheng says. A third-party company could analyze the incoming data, freeing internal IT teams from the job.

Among the challenges are standards for different data streams, Sheng says. Data streams could be in many formats, but they must be synonymous, or able to communicate with one another. Another challenge is acceptance. For large turbine OEMs, it may be manageable task to adopt new models of information sharing and gathering, but for smaller owner-operators, the challenge may be too much. Security is a challenge any time the Internet is involved.

Still, the industry has come a long way in a short time. In 2009, Sheng says, condition monitoring systems were hardly discussed. Today, some turbine manufacturers include dedicated condition monitoring systems on every turbine sold. In Europe, policy mandates condition monitoring systems. Conversations during AWEA Windpower 2014 seemed to indicate the challenges for big data could be overcome in a few years if advocates can convince the industry of its benefits.

“This is an opportunity for the industry,” Sheng says. “By compiling data using the big data concept, you may gain additional insights on ways to improve efficiency, profits, and make smarter business decisions.”

Of course, OEMs and owner-operators have relied on data for years. Turbines broadcast wind speed to data centers, letting utilities accurately forecast power production.

Software uses data to optimize plant layout and identify the best location for a wind farm. To pinpoint installations, Vestas uses software and a supercomputer to analyze many terabytes that include weather reports, tidal phases, geospatial and sensor data, satellite images, deforestation maps, and weather modeling. A wind farm analysis, which once took weeks, is now done in less than an hour.

Companies are beginning to harvest and analyze of data on a turbine-by-turbine and plant-by-plant basis to predict maintenance needs and increase turbine efficiency.

Siemens, for instance, will open a remote diagnostic center in Denmark this fall. The facility will house 150 analysts monitoring more than 7,500 wind turbines. Experts will analyze data and predict health and availability of turbines, preventing unscheduled downtime, and increasing O&M efficiency.

GE’s wind software uses plant-level data to improve overall wind-farm output. Using turbine-to-turbine communications, GE software lets turbines within a farm act as a cohesive unit, rather than individual assets. Wind plant wake management, for instance, is the first farm-level management application launched by GE that lets customers recapture lost power output from waking effects.

“In the past, wind plants have operated as autonomous units. With wind plant management, turbines can operate as part of an interconnected, cohesive team, as opposed to competing with one another for the best wind,” says Anne McEntee, president and CEO of GE’s renewable energy business. “Now, what used to be a series of 1 to 2 megawatt machines can operate more efficiently as a full-scale multi-megawatt power plant.” WPE

Filed Under: Sensors

Good summary Steven. I think in order for the data analysis to be most use, this has to be performed by thrid parties – OEM’s only really pursue data analysis to maximise availability (their contractual target) rather than maximise what the wind farm owner wants which is production (actually profit, but production has a greater effect on profit than availability). Conversely the wind farm owner often actually has little interest in predictive maintenance due to the availability gurantee offered by OEMs and the fact that many wind farm owners do not manage the servicing of their wind farms.

Many wind farmers do not dedicate much resource to analysing their data and often wind farms are only a minor part of their portfolio.

Check out http://www.scadaminer.com/applications/wind-turbine-scada-analysis/ for some examples of insights to be gained from wind farm SCADA data analysis.

Regards,

Tom