This is the introduction to a white paper on distributed energy resources from ABB.

Whether a utility is adding conventional or renewable distributed energy resources (DERs) to their system, successful integration requires a fundamentally different approach than when adding conventional base load generation.

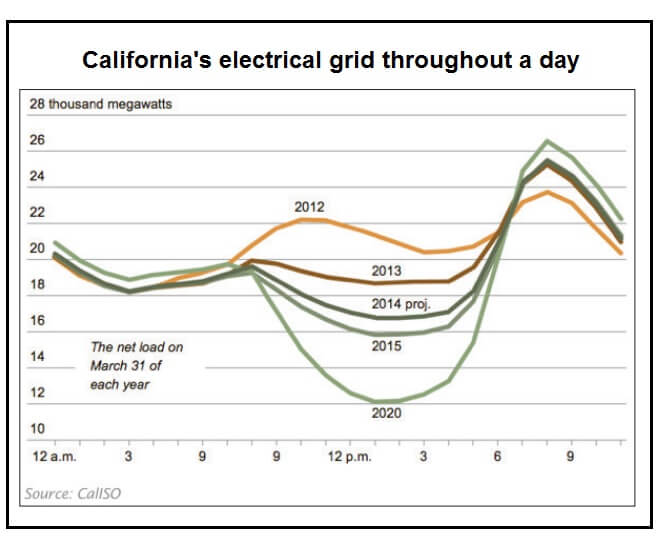

The so-called “duck” chart shows net supply and demand on the California grid in from 2012 to 2013, and forecast through 2020.

This is especially true if the penetration level of such generation is already large or expected to increase significantly in the not-too-distant future. In all likelihood, the proliferation of DERs (wind, solar, combined heat and power, microgrids, energy storage, and someday even electric vehicles) will necessitate the development of a smarter grid – one that can coordinate and balance these various technologies under a variety of operational constraints to:

a) mitigate technical challenges such as the variability of renewable generation;

b) support grid stability and reliability; and

c) maximize benefits to consumers and other stakeholders. In spite of the challenges utilities confront in creating a smart grid, the effort promises significant benefits above and beyond the expansion of renewable energy. As a recent report for the California Energy Commission (CEC) notes: “The investment in doing so… is desirable or even necessary for reasons other than reducing carbon emissions – namely, economy and reliability of electric service.”

In its report, “Reforming the Energy Vision,” the New York State Dept. of Public Service looks at the benefits of this approach at the distribution level: “The intelligent integration of DER can solve distribution system planning challenges and improve the resilience of distribution systems. For example, installation of distributed generation (DG) could potentially increase the useful life of existing feeders by reducing their loading… and accommodate localized load growth without the need to upgrade feeders.”

The report also notes that this is particularly the case with microgrids, which “may also employ an energy management system to balance generation and load, optimizing efficiency and ensuring critical loads within the microgrid remain energized.”

Furthermore, says Gary Rackliffe, ABB’s V.P., Smart Grids, North America, “microgrids can make DERs more dispatchable. For example, by using a microgrid to co-locate solar PV and energy storage (battery energy storage or flywheel energy storage), variability of the solar PV can be better managed to achieve compliance with grid codes.” Whatever the motivation for developing DERs, integration issues and complexity increase in step with their level of penetration.

And it’s not only in the Sun Belt that this is topic of discussion. As ISO New England noted a year ago: “Until recently, policy and industry indicators suggested that [DERs] would not have a substantial impact on system planning and system operations for a number of years; recent indicators suggest a different outlook.”

(Note: On May 1, 2013, the state of Massachusetts announced that it had quadrupled its solar PV goal, from 400 to 1,600 MW by 2020.) And further, ISO-New England noted, “DERs can impact transmission, even in small amounts: Location matters.”

Read the rest: https://goo.gl/aJnwRx

Filed Under: Policy