For wind farm owners, drones or unmanned aerial inspector, could be as good as a “$10,000 off your next blade inspection” coupon. Carrying 24-megabit pixel cameras or high-def video, inspecting blades is just their first assignment.

Paul Dvorak / Editor

Quadcopters and similar remote-controlled air vehicles have been available for years. YouTube is full of hobbyists flying quad-copters with GoPros showing the world what their neighborhood looks like. Entrepreneurs immediately saw the potential: inspect wind-turbine blades and other not-easy-to-inspect facilities using high-resolution cameras mounted on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, UAVs. Of course, the whole point of doing so is to inspect more blades in a shorter period and chip away at wind-farm operating expenditures.

The AAIR drone will carry a camera capable of 25-megapixel images. The frame is wider at one end to accommodate an unobstructed view for the camera.

Until recently, a reliable blade inspection was done by a wind tech hanging from a rope, and he might take six hours to inspect one turbine. An alternative might have been to use a crane or man bucket. But both options are expensive. And ground-based cameras need wind to manipulate the turbine rotor for a best shot. Even a telescope on the ground does not yield good imagery.

The basics and then some

Drones, for our purposes, are really UAVs capable of carrying high-resolution images and video, and soon sensors that might spot a range of problems in wind-turbine blades.

AAIR’s Grant Leaverton, the new breed of wind tech, flies a drone for a wind turbine inspection. He says that blade inspections are just the first of the services drones will provide to take cost out of wind farm O&M.

A wind technician with his new robot buddy will perform the inspection job, all three blades with guidance, in about 90 minutes, say technicians with WindSpect,

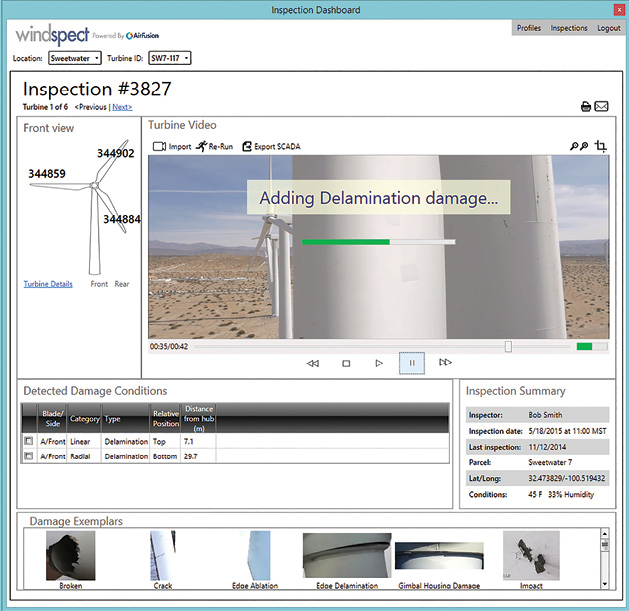

A wind technician with his new robot buddy will perform the inspection job, all three blades with guidance, in about 90 minutes, say technicians with WindSpect, one company flying drones. At the end of a flight, the technician will remove an SD card from the drone and put it into the company computer for a detailed report on what the inspection found. Specialized software has the capability to recognize flaws in the blade, mark their location as meters from the tip or ground, and identify the type of flaw, such as surface impact, cracks, or leading-edge erosion and more.

“We will release Version 1.0 of the AirFusion Wind Edition software mid-summer,” says AirFusion CEO Dennis Chateauneuf. He said that the solution has generated an extraordinary amount of interest and “dozens of productive conversations are taking place with owner-operators, wind-turbine manufacturers, and many of the service companies with a great deal of interest coming from Europe and Asia.”

“We are largely agnostic about the drone used in the inspection. Many platforms can carry the appropriate sensors, and meet the overall need for accurate flight, durability, and so on. We will suggest a variety of UAV choices that will be technically suitable to the task,” says AirFusion Chief Strategy Officer Kevin Wells.

An enormous advantage is that the software’s accuracy improves over time. “The more images it ‘sees’ and learns from, the better the end result. For example, if after using the AirFusion platform a company has archival footage that spans two or more years, the system may be able to indicate there is a crack in this location today that was not present a year ago. Was there a precursor we might have picked up to predict this problem? It could be something subtle, perhaps something under the surface of the blade. This temporal analysis is another benefit we will exploit to constantly improve the performance of the software. The system is smart today, but will become smarter over time,” says Greg Pepus, AirFusion’s SVP of Software Development.

Collision avoidance

UpWind Solutions, an independent operations and maintenance service provider for the wind industry, recently added blade inspections using UAVs to its services by partnering with SkySpecs. Both companies say the partnership will deliver high-quality images for reports, improving safety and reducing inspection costs.

SkySpecs says it provides an advanced UAV for easy completion of turbine blade inspections. What’s more, SkySpecs’ collision avoidance technology lets technicians with minimal flight training or experience conduct high-quality inspections from only a few feet away from the blade without risk of collision.

UpWind said a few other benefits of the technology include autonomous flight software that lets the company rapidly complete high-quality, low-risk inspections. High-definition images and video are produced for reports and to let users zoom in closely to problem points identified throughout the inspection. A technician can take control over the automated UAV any time to capture more images of a specific blade area.

25-mega-pixel images

Grant Leaverton, General Manager with UAV inspection company Advanced Air Inspection AAIR, has readied 6 and 8-rotor UAVs that can carry 25-mega-pixel cameras aloft, and conduct research on several other useful diagnostic sensors.

The blade image from AAIR shows sever trailing edge damage. The image is typical for those captured by drone carried cameras.

“Typically the more rotors the more stable the platform. Weight extracts its cost in flight time. The heavier the payload, the shorter the flight time. But what we can do now is the tip of an iceberg for industrial infrastructure inspections. For the time being, most will focus on the high-resolution inspection of blades, nacelles, and towers — the places that are not easy to reach,” he said.

The number of blades examined in a day depends on the type of inspection, “When focused on a particular feature, say the leading edge and looking for erosion, you can do 12 to 20 blades in a day depending on the height of the tower. But that is better than two per day with rope access or cranes. And if you want to cover every inch of blade, that of course takes more time,” said Leaverton.

Another plus: You can fly the UAV regardless of where the turbine rotor stops. “This is more of a personal preference issue. However, because we are taking pictures, we get the best lighting for photography with the blades pointing straight down. However, in a no-wind situation, you cannot turn or position the rotor but you can still do the inspection,” he said. The platform is easier to fly without wind.

While visual inspections are the obvious application, other sensors are getting auditions. One intriguing technology is infra-red. “If you are looking for internal defects that are barely subsurface, an infrared camera might reveal them. That’s the theory. Also, if the blade has delaminations, subsurface cracks, or wrinkles in the fiberglass, that will show up as a heat signature. The thinking is that such flaws will have to be close to the surface to show up, and depend on the sensitivity of the equipment,” explained Leaverton. “It’ is an interesting potential because internal defects are huge issues for owners. The defects are hard to detect and they can propagate and turn into catastrophic failures. So detecting internal defects will be a curious proposition.”

A typical screen from AirFusion shows a portion of an inspection report possible from a Windspect flight. Developer Greg Pepus says the software will provide analysis of images such as severity of damage and location indicators. IR cameras may soon provide other possibilities, such as internal blade damage.

There is also more around the wind farm that needs inspection. “A lot of wind-farms owners operate their own transmission lines and substations. The visual inspections are a big deal, along with infrared thermal imaging for detecting hot spots or broken insulators. Another sensor to detect corona discharges would indicate broken hardware such as insulators.”

For utilities, keeping the right-of-way open is critical. For example, it’s important to keep transmission lines free of vegetation, trees over lines, overgrowth, and encroachment. Infrared is also good for looking for vegetation.

Ideas for improvement

Leaverton suggests improving a few things. For example, knowing where one picture out of hundreds came from is important. “Before starting an inspection, you must know which blade you are looking at, and identify the hub. So before the inspection, we find a way to ID the blade. We use a light board on which we write, Blade 1.” This issue is handled different from company to company.

Because where you are on the blade is also an issue, industry guidelines would prove useful. “A problem is that blades have no reference lines on them. Some have markings and others have lightning protection that serves as a landmark. In absence of reference marks, we use geo tagging in each photo so we know the altitude at which each picture was taken. That works best when the blade is straight down.

Measuring defects is also more art than science at this time. You have go on the relative features of the blade and understand the width of the frame. “It’s necessary to maintain a steady distance from the blade so you know, for instance, that each frame represents one meter. But that is imperfect so in the report, we relate damages with respect to each other rather than absolute measurement.”

When a pilot of the UAV has a video screen to see what UAV is seeing, “You get a first person video perspective of what the camera sees. When using a two-man crew, one might use goggles, so both would look at a blemish and discuss the problem. Once you get the picture on the computer you can look even closer because the high resolution allows zooming in on the area of interest,” he said.

In the end, the goal is to better allocate repair dollars. “Wind-farm owners won’t fix everything, but if we can identify the worst of things, that is useful. And that is a value-add,” said Leaverton.

On the horizon

More sensors in development might identify water in the blade or spot where the laminations are coming apart, or to carry RFID sensors if it is necessary to do some sort of inventory management.

“We are hard at work evaluating a wide variety of sensor types in our lab today,” said AirFusion’s Chateauneuf. “The ultimate goal is to be able look under the surface, to look inside the blade. So we’re working on that and other sensor-based techniques to add functionality for future releases like truly automated flight control where the UAV effectively “flys itself” around the blade to collect the data automatically.”

Later, an automated flight control feature will let the drones fly themselves in a pattern around the blades. This is subject to FAA regulations because flight control is one of those things that are only done with permission. “But we are working on that because of its great potential,” added Wells.

Fly-it-yourself is another possibility said Leaverton. “If a wind farm wants to buy a UAV, we’ll be glad to provide flight instructions.”

In addition to inspections, it’s not hard to imagine the drones doing cosmetic repair in a year or two and more serious repairs after that. This is all good news for the wind industry because the speed, accuracy, and detail will shave more off O&M costs making wind-generated power all the more competitive with other generators of electricity.

For a digital copy of the entire June issue of Windpower Engineering & Development, click here.

Filed Under: Featured, O&M